Testosterone Therapy and Erythrocytosis • The Blood Project

Introduction Androgens play a crucial role in the development and maintenance of: Male reproductive and sexual functions Body composition Erythropoiesis

www.thebloodproject.com

www.thebloodproject.com

Introduction

- Androgens play a crucial role in the development and maintenance of:

- Male reproductive and sexual functions

- Body composition

- Erythropoiesis

- Muscle and bone health

- Cognitive function

- Testosterone falls progressively with age and a significant percentage of men over the age of 60 years have serum testosterone levels that are below the lower limits of young adult men.

- Low levels of circulating androgens may result in:

- Reduced male fertility

- Sexual dysfunction

- Decreased muscle formation

- Bone mineralization

- Disturbances of fat metabolism and cognitive dysfunction

- Symptomatic hypogonadal patients may benefit from testosterone treatment

- Proposed benefits of testosterone therapy include:

- Improved sexual function

- Improved bone mineral density

- Increased strength

- Improved lipid profiles

- Testosterone has a dose-dependent stimulating effect on erythropoiesis.

- Erythrocytosis is the most common dose-limiting effect of testosterone therapy.

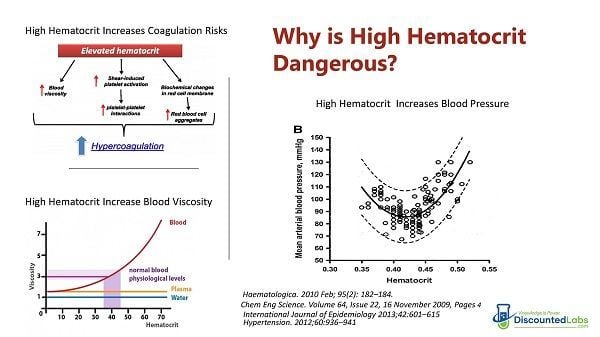

- Erythrocytosis confers an increased blood viscosity and potential (though unproven) increased risk of thromboembolic events.

Definitions

- Testosterone deficiency syndrome, also known as late-onset hypogonadism, is a clinical and biochemical syndrome that can occur in men in association with advancing age. The condition is characterized by deficient testicular production of testosterone due to pathology at one or more levels of the hypothalamic–pituitary–testicular axis. It may affect multiple organ systems and can result in substantial health consequences.

- Polycythemia:

- An erythrocyte mass exceeding 125% predicted based on sex and body mass

- Hematocrit of 48% – 55% (threshold differs according to guideline organization)

- May be divided into:

- Primary:

- Also known as polycythemia vera

- Caused by an over-production of erythrocytes secondary to intrinsic cellular defects within the bone marrow (almost always associated with mutation in JAK2)

- Secondary:

- Physiological response to decreased tissue oxygenation

- Inappropriate stimulation of erythropoiesis, such as with testosterone therapy

- Erythrocytosis often used interchangeably with polycythemia, but actually refers to increased red blood cell count.

Testosterone deficiency syndrome

- Clinical presentation includes:

- Sexual symptoms:

- Decreased libido

- Erectile dysfunction

- Decreased frequency of morning erections

- Fatigue

- Diminished work and/or physical performance

- Decreased muscle mass and strength

- Decreased body hair

- Increased body fat

- Depression

- Sleep alterations

- Impaired memory

- Irritability

- Poor concentration

- Metabolic disorders:

- Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Obesity

- Mild anemia

- Risk factors for hypogonadism in older men may include:

- Chronic illnesses, including:

- Diabetes mellitus

- Chronic obstructive lung disease

- Inflammatory arthritic, renal and HIV-related diseases

- Obesity

- Metabolic syndrome

- Hemochromatosis

- Diagnosis:

- A diagnosis of male hypogonadism must comprise both:

- Persistent clinical symptoms

- Biochemical evidence of testosterone deficiency

- Guideline definitions:

- European Association of Urology (EAU):

- Hypogonadism is diagnosed on the basis of persistent signs and symptoms related to androgen deficiency and assessment of consistently low testosterone levels (on at least two occasions) with a reliable method.

- Measure testosterone in the morning before 11.00 hours, preferably in the fasting state.

- Endocrine Society:

- We recommend diagnosing hypogonadism in men with symptoms and signs of testosterone deficiency and unequivocally and consistently low serum total testosterone and/or free testosterone

concentrations - Clinicians should measure total testosterone concentrations on two separate mornings when the patient is fasting (testosterone concentrations exhibit significant diurnal and day-to-day variations and may be suppressed by food intake or glucose).

- American Urological Association (AUA):

- Clinicians should use a total testosterone level below 300 ng/dL as a reasonable cut-off in support of the diagnosis of low testosterone.

- The diagnosis of low testosterone should be made only after two total testosterone measurements are taken on separate occasions with both conducted in an early morning fashion.

- The clinical diagnosis of testosterone deficiency is only made when patients have low total testosterone levels combined with symptoms and/or signs.

- ISA, ISSAM, EAU, EAA and ASA:

- A serum sample for total testosterone determination should be obtained between 07.00 and 11.00 h.

- The most widely accepted parameters to establish the presence of hypogonadism is the measurement of serum total testosterone.

- There are no generally accepted lower limits of normal. There is, however, a general agreement that total testosterone level above 12 nmol/L (350 ng/dL) does not require substitution. Similarly, based on the data of younger men, there is consensus that patients with serum total testosterone levels below 8 nmol/L (230 ng/dL) will usually benefit from testosterone treatment. If the serum total testosterone level is between 8 and 12 nmol/L, repeating the measurement of total testosterone with sex hormone binding globulin to calculate free testosterone or free testosterone by equilibrium dialysis) may be helpful (see 3.5 and 3.7 below).

- European Association of Urology (EAU):

- Treatment:

- Treatment involves testosterone supplementation in most cases.

- The goals of testosterone treatment include:

- Improvement in symptoms (improve quality of life).

- Achievement of eugonadal levels of testosterone (restore testosterone levels to the physiological range).

- Available safe and effective preparations include:

- Intramuscular

- Subdermal

- Transdermal

- Oral

- Buccal

- Adverse effects include:

- Erythrocytosis

- Cardiovascular events and venous thromboembolic events:

- The evidence for increased risks of arterial and venous events is controversial.

- Amongst randomized controlled trials (RCTs), meta-analyses do not support an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events.

- None of these trials evaluated secondary polycythemia as a potential independent risk factor for these adverse events.

- Prostate cancer – the relationship between testosterone therapy and the development of prostate cancer has been debated.

- Cardiovascular events and venous thromboembolic events:

Epidemiology of testosterone therapy-associated erythrocytosis

- Erythrocytosis is the most frequent adverse event reported in randomized control trials of testosterone therapy.

- Men receiving testosterone therapy have a 315% greater risk for developing erythrocytosis when compared to control.

- Prevalence of erythrocytosis (hematocrit > 0.50) in testosterone-treated hypogonadal cis men ranges between 5% and 66%.

- Risk factors for developing erythrocytosis after testosterone therapy include:

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Advanced age

- Obesity

- Type II diabetes mellitus

- Elevated baseline hematocrit (>50%)

- Those who live in high altitudes

- Testosterone formulation, dose and pharmacokinetics

- Short-acting intramuscular (IM) formulations result in supraphysiological testosterone levels achieved days after administration.

- Extended-release injectable testosterone and transdermal options maintain physiological testosterone levels more effectively and reduce the risk of secondary erythrocytosis.

- Risk/rate of erythrocytosis according to formulation:

- Intramuscular injections – 40%

- Subcutaneous pellets – 35%

- Transdermal – 15%

- Androgel – 3%

- Intranasal testosterone – 0–2%

- Oral testosterone – 0.03%

- Risk/rate of erythrocytosis according to formulation:

Pathophysiology of testosterone therapy-associated erythrocytosis

- The mechanisms underlying testosterone therapy-associated erythrocytosis are poorly understood.

- Testosterone therapy has been associated with:

- Dose-dependent decrease in hepcidin, which is hypothesized to increase absorption of iron, iron availability and erythropoiesis.

- Increased erythropoietin levels.

- Increased levels of estradiol, a breakdown product of testosterone via aromatase, which increases hematopoietic telomerase, resulting in increased hematopoietic stem cell proliferation and survival.

Clinical presentation of testosterone therapy-associated erythrocytosis

- Objective increases in hematocrit noted after one month of therapy.

- Erythropoiesis tends to occur primarily in the first 6 months of treatment and then reaches a plateau.

- The largest increase typically seen in the first year after initiation of testosterone therapy.

- The hematocrit and hemoglobin tend to return to baseline after 3–12 months once testosterone therapy is discontinued.

Complications/risks of testosterone therapy-associated erythrocytosis

- Erythrocytosis can lead to increased blood viscosity.

- While primary erythrocytosis has been well established as a risk factor for thromboembolic events, the risk of secondary erythrocytosis related to testosterone therapy is less clear.

- In a meta-analysis of all randomized controlled trials for testosterone therapy and cardiovascular risk, the existing evidence was not found to support a causal role between testosterone therapy and adverse CV events when hypogonadism is appropriately diagnosed and treated. However, none of these trials evaluated secondary polycythemia as a potential independent risk factor for these adverse events.

- There are no randomized or prospective studies that have documented a direct relationship between testosterone therapy-related erythrocytosis and thromboembolic events.

Hematocrit thresholds and indications for intervention

- The Endocrine Society:

- Hematocrit threshold of > 50% is relative contraindication to initiating testosterone therapy.

- Testosterone therapy can cause erythrocytosis (hematocrit > 54%).

- Hematocrit threshold of >54% is an indication to discontinue treatment.

- Clinicians should evaluate men who develop erythrocytosis during testosterone-replacement therapy and withhold testosterone therapy until hematocrit has returned to the normal range and then resume testosterone therapy at a lower dose.

- Using therapeutic phlebotomy to lower hematocrit is also effective in managing testosterone treatment–induced erythrocytosis.

- The European Association of Urology (EAU):

- The clinical significance of a high hematocrit level is unclear, but it may be associated with hyperviscosity and thrombosis.

- If testosterone is prescribed then testosterone levels should not exceed the mid-normal range and the hematocrit should not exceed 54%.

- Monitor testosterone, hematocrit at three, six and twelve months and thereafter annually.

- If the hematocrit is above 54%:

- Decrease the testosterone dosage or switch testosterone preparation from intramuscular to topical or venesection.

- If hematocrit remains elevated, stop testosterone and reintroduce at a lower dose once hematocrit has normalized.

- Venesection (500 mL) may be considered and repeated if necessary.

- The hematocrit value of > 54% is based on the increased risk of cardiovascular mortality from the Framingham Heart Study.

- ISA, ISSAM, EAU, EAA and ASA:

- Men with significant erythrocytosis (hematocrit >52%), untreated obstructive sleep apnea, untreated severe congestive heart failure should not be started on treatment with testosterone without prior resolution of the co-morbid condition.

- Erythrocytosis can develop during testosterone treatment, especially in older men treated by injectable testosterone preparations. Periodic hematological assessment is indicated, i.e. before treatment, then 3–4 and 12 months in the first year of treatment and annually thereafter.

- Although it is not yet clear what critical threshold is desirable, dose adjustments and/or periodic phlebotomy may be necessary to keep hematocrit below 52–55%.

- European Academy of Andrology (EAA):

- We suggest against TRT in men with documented polycythemia and/or elevated hematocrit (>48%-50%) depending on CV risk and associated morbidities without further evaluation.

- If Hct is >54%, TRT should be discontinued, until Hct decreases to a safe level; evaluate the patient for hypoxia and sleep apnea; reinitiate therapy with a reduced dose.

- There is a general consensus that Hct > 54% requires TRT withdrawal (and sometimes phlebotomy) to minimize the risks of VTE and CV events.

- American Urological Association (AUA):

- Prior to offering testosterone therapy, clinicians should measure hemoglobin and hematocrit and inform patients regarding the increased risk of polycythemia.

- Prior to commencing testosterone therapy, all patients should undergo a baseline measurement of hemoglobin/hematocrit. If the Hct exceeds 50%, clinicians should consider withholding testosterone

therapy until the etiology is formally investigated. - While on testosterone therapy, a Hct 54% warrants intervention, such as:

- Dose reduction

- Temporary discontinuation

- While the incidence of polycythemia for one particular modality of testosterone compared to another cannot be determined, trials have indicated that injectable testosterone is associated with the greatest treatment-induced increases in hemoglobin/Hct.

Note: hematocrit of ≥54% appears to be consistent threshold to discontinuing or reducing treatment utilized by major urologic governing bodies, while the evidence for this specific cutoff is lacking.