COMMENTARY ON THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Aging is variably but inevitably accompanied by declines in health; concomitantly, in men, circulating sex-steroid levels fall with age.

1 To what extent these two processes are causally linked and whether testosterone therapy can prevent or ameliorate important age-related problems have been major issues in men's health. In 2003, a committee assembled by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) found a paucity of randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials involving older men and noted a lack of definite evidence that testosterone therapy conferred benefits.

2 The committee recommended that clinical trials be initiated, first to evaluate the efficacy of testosterone supplementation in older men and then to assess long-term benefits and risks through large-scale trials.

Little has changed to alter the conclusions of that report; if anything, the issue of testosterone supplementation has become more controversial.

3 However, in this issue of the

Journal, Snyder et al.

4 describe the long-awaited initial results of the National Institutes of Health–sponsored Testosterone Trials, which were designed to address the key issues identified by the IOM. Their report is important, not only because it deals with an essential public health issue but also because the investigators have succeeded in conducting the kind of generally well-conceived studies that are sorely needed in the field. The findings begin to provide a basis for more rational clinical decisions about testosterone use as well as for additional research.

The overall design of the Testosterone Trials is complex.

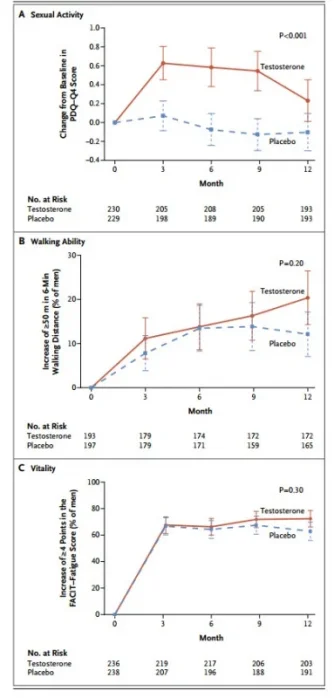

5 It includes seven independent, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials intended to address specific outcomes that are postulated to be related to testosterone deficiency (sexual function, vitality, physical function, cognitive function, anemia, bone density, and cardiovascular status). The trials are knitted together by common methods and some shared measures, thus maximizing the power of the overall investigation. This inaugural report describes the findings of the three main studies (with primary outcomes related to sexual function, physical function, and vitality).

The results show that testosterone therapy did yield certain benefits, but at this point their clinical importance is uncertain. Therapy was not a panacea, and the findings alone might be insufficient to support a decision to initiate testosterone therapy in symptomatic older men. The study confirmed that testosterone supplementation can yield improvements in sexual function, but the benefits were modest, tended to wane in the latter months of the treatment period, and, as the authors note, were not as robust as those of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors.

6 There were only small gains in physical performance and in indexes of mood and depression; overall vitality was no better with testosterone therapy than with placebo. For each of the outcomes, some older men may have a more vigorous response to testosterone therapy and thus could be more attractive candidates for supplementation; however, it was not possible to confidently identify them by the testosterone levels achieved with therapy. As expected, estradiol levels also increased; those levels have been linked to key health variables in men (e.g., sexual function).

7 It's not yet clear whether responses (or the lack thereof) in the Testosterone Trials may be due to changes in estradiol levels.

There is considerable controversy about possible adverse effects of testosterone therapy in older men, and these studies do not resolve this controversy. Although there were minor effects on hemoglobin and prostate-specific antigen levels, and, reassuringly, no apparent major toxic effects, larger and more extended trials would be needed to determine whether therapy has negative effects on outcomes such as prostate or cardiovascular health.

Importantly, the study participants were recruited on the basis of stringent criteria (age ≥65 years, total testosterone levels below the normal range in men 19 to 40 years of age [<275 ng per deciliter], symptoms related to predetermined outcomes, and no contraindications to participation). Only 1.5% of those screened (790 of 51,085 men) were eligible and enrolled. The average participant was 72 years of age; almost 90% of participants were white, most were obese, most had hypertension, more than one third had diabetes, and almost 20% had sleep apnea. The select nature of the participants reflects the scientific rigor of the trials (and the causes of low testosterone levels) but also clearly limits the generalizability of the conclusions. We should not assume that the benefits, lack of benefits, or adverse-event profile observed in these studies would be similar in younger men (most testosterone prescriptions are written for middle-aged men

3), men with higher testosterone levels, or those with different demographic or clinical characteristics.

The report by Snyder et al. is likely to stimulate controversy and to engender additional research questions — as did the Women's Health Initiative with respect to estrogen-replacement therapy. Nevertheless, it is a landmark study in the field of men's health and no doubt a bellwether for additional important contributions from the Testosterone Trials.''

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMe1600196