madman

Super Moderator

* read full paper (pdf)

MECHANISMS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY

Estradiol as a male hormone

Nicholas Russell and Mathis Grossmann

Abstract

Evidence has been accumulating that, in men, some of the biological actions traditionally attributed to testosterone acting via the androgen receptor may in fact be dependent on its aromatization to estradiol (E2). In men, E2 circulates at concentrations exceeding those of postmenopausal women, and estrogen receptors are expressed in many male reproductive and somatic tissues. Human studies contributing evidence for the role of E2 in men comprise rare case reports of men lacking aromatase or a functional estrogen receptor alpha, short-term experiments manipulating sex steroid milieu in healthy men, men with organic hypogonadism or men with prostate cancer treated with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and from observational studies in community-dwelling men. The collective evidence suggests that, in men, E2 is an important hormone for hypothalamic–pituitary–testicular axis regulation, reproductive function, growth hormone insulin-like growth factor-1 axis regulation, bone growth and maintenance of skeletal health, body composition and glucose metabolism and vasomotor stability. In other tissues, particularly brain, elucidation of the clinical relevance of E2 actions requires further research. From a clinical perspective, the current evidence supports the use of testosterone as the treatment of choice in male hypogonadism, rather than aromatase inhibitors (which raise testosterone and lower E2), selective androgen receptor modulators and selective estrogen receptor modulators (with insufficiently understood tissue-specific estrogenic effects). Finally, E2 treatment, either as add-back to conventional ADT or as sole mode of ADT could be a useful strategy for men with prostate cancer.

Introduction

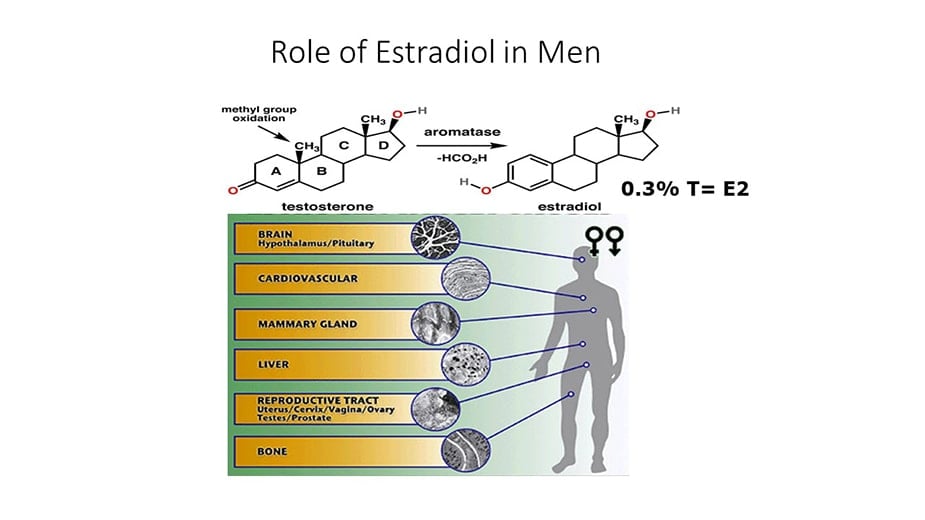

Estrogens were demonstrated in the urine of men in the 1920s (1) and in the testis in 1952 (2). In 1937 Steinach and Kun demonstrated that administration of large doses of testosterone to men increased the estrogenic activity of their urine and inferred in vivo conversion of testosterone to estrogens (3). Subsequent advances included the identification, isolation, sequencing and regulatory characterization of the aromatase cytochrome P450 enzyme, product of the CYP19A1 gene, the enzyme responsible for aromatization of testosterone to 17β estradiol (E2) and androstenedione to estrone (E1), the major endogenous estrogens (4). Many other non-aromatized endogenous steroids, estrogen metabolites and environmental and pharmaceutical compounds with diverse structures have minor estrogenic activity (5, 6).

Physiology and metabolism of estrogens

Circulating E2 in men

One quarter to one half of circulating E2 is estimated to originate from direct testicular secretion, with the rest resulting from peripheral aromatization of testosterone, particularly in adipose tissue, muscle, bone and brain (7, 8, 9). Median serum E2 concentrations are around 150 pmol/L in healthy young men and 90 pmol/L in healthy older men, compared to 400 pmol/L in premenopausal women, while healthy male circulating testosterone concentrations are substantially higher, ranging from about 10 to 30 nmol/L, although these concentrations vary across studies performed in different populations and using different assay methodologies (10, 11).

Metabolism of estrogens

The predominant metabolic pathway for E2, the most potent endogenous estrogen, is reversible oxidation to E1 by the widely distributed 17β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (12). For infusions of labeled steroid, oxidation of E2 to E1 is more rapid than the reductive reaction (13). E2 and E1, the parent estrogens, undergo irreversible hydroxylation at the 2-, 4- or 16-carbon positions by cytochrome P450 enzymes, particularly CYP1A2 and CYP3A4, located in the liver and other tissues (14). The 4-hydroxy-estrogens are similar in potency to the parent estrogens, while the 2-hydroxy-estrogens are less potent and therefore, because they retain ER-binding affinity, may be relatively anti-estrogenic (15). The 2- and 4-hydroxylated metabolites undergo methylation to less active forms (16). The 16α hydroxyestrogens, including estriol (E3), retain minor estrogenic activity (17).

Estrogen receptors in men

ERα and ERβ, encoded by the ESR1 and ESR2 genes respectively, are members of the nuclear receptor superfamily. Multiple isoforms of each receptor type exist, created by differential splicing of exons (19). More recently, the transmembrane G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER) was identified (20). ERs are expressed throughout the human male reproductive tract, and also in male brain, cardiovascular system, liver, bone, adipose tissue, pancreatic islets and skeletal muscle (21).

Intracrinology of estrogens

Most clinical studies infer biological actions from serum E2 concentrations, based on the classical endocrine concept that gonadal-produced sex steroids circulate to target tissues to exert their effects. These studies do not take into account cellular uptake, either after dissociation from SHBG or albumin or perhaps as an SHBG-bound complex (24), nor local production and metabolism of sex steroids in target tissues themselves, with potential for autocrine and paracrine actions. As reviewed elsewhere (25), some extragonadal tissues possess the capacity for de novo sex steroid synthesis and/or for metabolism of circulating precursors, such as adrenal produced dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, and express steroidogenic enzymes not reported to be active in gonadal tissues. The net biologic effects of such locally acting estrogenic compounds in individual target tissues are not known but, in combination with the use of inaccurate immunoassays, may contribute to the relatively modest associations of circulating E2 concentrations with biologic phenotypes reported in many clinical studies.

Hypothalamic–pituitary–testicular axis regulation

Overall, human studies suggest that E2-mediated negative feedback on gonadotropin activation involves both hypothalamic and pituitary actions. Moreover, while E2 is important for this negative feedback, it is likely that AR-mediated effects also play a role.

Reproduction

Spermatogenesis

A comprehensive discussion of the role of E2 in testicular function and spermatogenesis is beyond the scope of this manuscript and recent reviews exist (21). Briefly, ERα and ERβ are expressed throughout the human male reproductive tract, including in germ cells, although there are conflicting data in certain cell types. Aromatase is found in human immature germ cells, spermatozoa, efferent ductules of the testis and epididymis (21). While studies in mice have demonstrated important roles for estrogen signaling in male fertility, studies in men have been less dramatic and less conclusive.

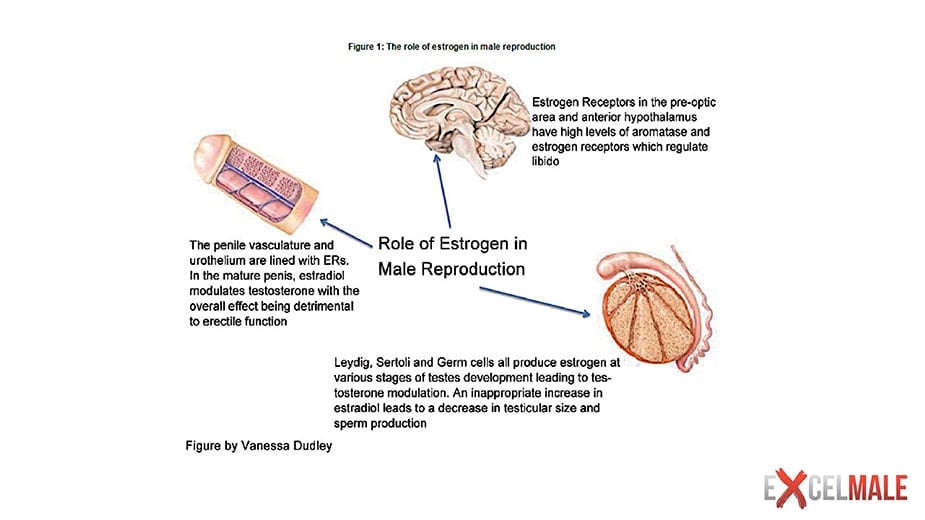

Libido and erectile function

The evidence from men with congenital non-functional ERα or aromatase deficiency suggests that E2 is not essential for male libido and erectile function (39, 46), but various lines of evidence support some physiological role. In non-blinded studies, two men with aromatase deficiency had increments in libido and sexual activity during E2 treatment, either alone (51) or with testosterone (47). Non-definitive evidence from men with prostate cancer suggests that androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) using estrogens may better maintain sexual function than surgical castration (52) and GnRH analogs (53).

Prostate

Estrogens are synthesized by aromatase in the prostate stroma (55) and have autocrine and paracrine actions. ERα appears to be primarily located in prostate stromal cells while ERβ is found primarily in the epithelium (56). GPER has been demonstrated in stromal cells and epithelial progenitor cells (57). Estrogens appear to have a role during normal prostate development in utero, a time of high systemic estrogen exposure (56, 57). However, unphysiologically timed or dosed estrogen exposure during prostate gland development influences later prostate cancer risk in animal models (58).

In summary, the collective evidence from rare case studies (including ER and aromatase-deficient men) and experimental studies in healthy younger and older men is consistent with the fact that ER signaling plays a role in various aspects of male reproductive health, including testicular descent, spermatogenesis and sexual function. ER signaling also has complex effects on the prostate gland, but the consequences for prostate health and disease are poorly understood.

Growth hormone insulin-like growth factor-1 axis

Men with congenital aromatase deficiency have impaired stimulated growth hormone (GH) secretion and low insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) (66). Exogenous E2 in these men was not able to normalize GH secretion (66), possibly because of abnormal development of the GH–IGF-1 axis in the setting of congenital E2 deficiency or because restoration of normal circulating E2 concentration is insufficient if local E2 production remains impaired (67). Additional lines of evidence from preclinical models, women, and indirect evidence from men, suggest that E2 is important in regulation of GH secretion by both direct and indirect mechanisms (67, 68).

In summary, E2 rather than testosterone appears the main sex steroid regulator of the GH-IGF-1 axis in men.

Bone

Osteoblasts, osteocytes, osteoclasts and marrow stromal cells contain ER and AR (72, 73). The weight of evidence points to E2, acting via ERα, as the predominant sex steroid in the development and maintenance of the male skeleton (74). Androgens have a smaller but important role, particularly in promoting periosteal apposition to increase bone size in men.

E2, linear bone growth, cessation of growth and achievement of peak bone mass

E2 has concentration-dependent effects on skeletal growth. Pre-puberty, serum and tissue E2 is extremely low, and skeletal growth, more appendicular than axial, is mediated by the GH–IGF-1 axis (76). Skeletal sexual dimorphism does not arise until puberty (77). Men are taller than women, predominantly because of a longer period of prepubertal growth, leading to longer leg length (78).

E2 and bone loss in older men and in models of hypogonadism

Severe hypogonadism in older men induces accelerated bone remodeling and deterioration in bone density and microarchitecture (91). Observational and experimental evidence suggests that these effects are mostly E2 dependent.

Serum E2 and fractures in men

In summary, the available data suggest that, while testosterone has direct effects on bone remodeling and bone microstructure, and indirect effects though anabolic effects on skeletal muscle, E2 appears to be the sex steroid predominantly important for skeletal health in men.

Body composition and glucose and lipid metabolism

Body composition: E2, muscle and fat

In men, aromatase activity is reported in skeletal muscle (114) and adipose tissue (9). Aromatase is strongly expressed in the stroma of human adipose tissue, although nearly all of these data are from women (115). ERs are also expressed in human adipose tissue (116) and there is low level expression of ERα in human skeletal muscle (117).

Effects of obesity on E2

Observational studies have consistently found a negative linear correlation between serum testosterone and body mass index in men (125). Insulin resistance lowers SHBG and therefore total testosterone, but as obesity increases, free testosterone also falls, and this is associated with low or inappropriately normal LH. One hypothesized mechanism is that in obesity, excess adipose tissue aromatase activity elevates E2 concentrations, which increases negative feedback on LH production. In the 1970s higher E1 and E2 serum concentrations and urinary production rates were reported in obese men compared with lean controls (126). However, there are little subsequent data to support the excess aromatization hypothesis. For example, a study by Dhindsa et al. employed mass spectrometry and equilibrium dialysis to accurately measure total and free E2 in obese men with type 2 diabetes with either subnormal or normal serum free T (127). Men with subnormal free testosterone had lower E2 concentrations than those with normal serum free testosterone. In Dhindsa’s study, and also in the European Male Aging Study in which men mostly did not have diabetes (128), testosterone and E2 concentrations were positively correlated.

Glucose metabolism

Subnormal serum testosterone is prevalent in men with type 2 diabetes. Contrary to the hypothesis that this low testosterone is due to negative feedback from elevated serum E2 produced by excessive adipose tissue aromatase, Dhindsa et al. showed that E2 in men with type 2 diabetes is low and remains directly correlated with serum testosterone (127)

Lipid metabolism

Roelfsema et al. performed a short-term clamp study to isolate the effect of physiological E2 concentration on lipids and inflammatory markers in healthy older men (140). This design avoided confounding effects of changes in body composition and physical activity. Over 3 weeks, 74 men were rendered acutely hypogonadal by a GnRH antagonist followed by randomization to IM testosterone add-back or placebo, AI or placebo, and transdermal E2 patch or no patch. Four groups were analyzed: IM placebo (T−E2−); IM T plus oral placebo (T+E2+); IM T plus oral AI (T+E2−) and IM T plus AI plus E2 patch (T+E2++). Mean serum testosterone concentrations were 14.9–17.3 nmol/L at baseline. The intervention produced testosterone concentrations of 5.7 nmol/L in the testosterone-E2 group, different from the 25.9 to 29.3 nmol/L in the three groups receiving testosterone add-back. Mean serum E2 concentrations were 77–99 pmol/L at baseline, then 4 pmol/L in the testosterone+E2− group, 35 pmol/L in testosterone−E2− group, 115 pmol/L in the T+E2+ group and 301 pmol/L in the T+/E2++ group. Despite an 80-fold range of serum E2 concentrations encompassing the physiological range, linear regression analysis showed that TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, lipoprotein (a) and apolipoprotein B were unrelated to serum E2 or testosterone concentrations. While larger studies are needed to confirm these findings, they suggest that the lipid changes observed in other studies might be due to body composition or activity changes, pharmacological rather than physiological actions or other confounders.

Vascular reactivity and atherosclerotic plaque

In summary, the data suggest that the metabolically beneficial effects of testosterone on body composition are mediated via aromatization of E2 to limit adiposity, including VAT, but that the anabolic effects of testosterone on muscle mass are largely a direct effect via AR signaling. With respect to sex steroid-mediated beneficial effects on insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism, experiments in male rodents and men indicate that these are, at least in part, mediated via E2 signaling in multiple metabolically active tissues. Inferences on effects on lipids and atherosclerosis are limited due to the lack of appropriately designed studies.

Brain

Antenatal effects on brain structure and gender-related behavior

Brain structure and physiology, and resultant cognition and behavior, are sexually dimorphic. The greatest distinctions pertain to structures and behaviors relevant to reproduction. These differences are attributable to differences in gonadal hormone secretion, and the effects of sex chromosome-encoded genes (144, 145, 146).

Cognition

In summary, while E2, acting locally, is critical for brain masculinization during development in rodents, in men, brain masculinization appears to track more closely with testosterone signaling via the AR, although data are limited. Whether sex steroids have effects on cognition is not clear.

Vasomotor stability

The profound sex steroid deficiency induced by ADT with GnRH analogs produces vasomotor symptoms (VMS) in the majority of men (155). In men, as in perimenopausal women, E2 withdrawal is the mediator of this effect. In women E2 withdrawal has been shown to cause release of hypothalamic neurokinin B, a paracrine regulator of heat dissipation effectors (156). In Finkelstein’s paradigm of experimental testosterone and E2 depletion in young men with differential add-back of testosterone with or without AI, men receiving AI had a greater incidence of VMS, and even supraphysiologic serum testosterone concentrations were unable to prevent hot flushes if serum E2 remained <37 pmol/L (157). In a preliminary report of an ongoing RCT comparing two modes of ADT for prostate cancer, high-dose transdermal E2 versus standard GnRH analog therapy, men in the E2 arm had a lower incidence of hot flushes at 6 months (8 vs 46%) (53). Finally, in a 4-week RCT, low-dose transdermal E2 add-back in men receiving GnRH analog therapy, reduced hot flush frequency-severity scores (104).

Effects of excess E2 in men

Excess exposure to estrogens in men can cause gynecomastia, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, and, if the exposure is pre-pubertal, premature epiphyseal closure leading to short stature. This phenotype occurs in the rare, autosomal dominant, aromatase excess syndrome that results from subchromosomal rearrangements that enhance aromatase transcription. (158). The first rearrangements were described in 2003 (159) but cases of familial gynecomastia, likely due to this syndrome have been noted since antiquity (160).

Gynecomastia is the most consistent effect of excess exposure to estrogens in boys and men. In addition to the aromatase excess syndrome, gynecomastia has been described in cases of estrogen-secreting testicular tumors (161) and Sertoli cell proliferation in Peutz Jegher Syndrome (162), excess aromatase expression by hepatocellular carcinoma (163), occupational exposures, abuse of aromatizable androgenic steroids and intentional pharmacological use of estrogens including in transgender women and in men with prostate cancer (164). Gynecomastia is also seen without absolute estrogen excess. Male breast tissue expresses both ER and AR. In females, estrogens stimulate breast tissue, whereas androgens inhibit it (165). This understanding has been extrapolated to men (166). Gynecomastia can occur in circumstances where there is absolute androgen deficiency or where the ratio of circulating free testosterone to free E2 is reduced (164). Examples of the latter include conditions in which SHBG is increased such as thyrotoxicosis or aging (because SHBG binds testosterone more avidly than E2, SHBG elevation reduces free testosterone more than it does free E2) (167).

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals

The Endocrine Society defines an endocrine-disrupting chemical (EDC) as an ‘exogenous chemical or mixture of chemicals, that interferes with any aspect of hormone action’ (171). Many EDCs, such as bisphenol A, p,p′-dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT, now banned), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs, now banned) bind to and activate ERs. Pre- and perinatal exposure to some of these EDCs, and others, have obesogenic, diabetogenic and reproductive effects in rodent studies and there is epidemiological evidence to support similar effects in humans (6). However, causation in humans has not been proven and EDCs can act through diverse mechanisms, including inhibition of androgen production and action, and direct toxic effects on endocrine and reproductive tissues. Therefore, it is impossible at present to isolate particular estrogenic effects of particular EDCs that are responsible for any particular clinical effect in men.

Tissues in which androgen action is independent of aromatization

In certain tissues, AR-mediated actions are clearly predominant. The in utero development of male external genitalia is AR mediated. Micropenis and hypospadias can occur in XY male infants with partial androgen insensitivity syndrome, and topical DHT, which is not aromatized, can produce penile growth (172). The higher male reference range for hemoglobin reflects the impact of androgen action on erythropoiesis. The mechanisms appear to be via AR-mediated reduction in hepatic hepcidin production, thus increasing iron availability for red cell production (173). Male-pattern body hair growth is also AR mediated, illustrated by the efficacy of 5α-reductase inhibitors for treating androgenic alopecia (174).

Clinical implications of E2 physiology in men

Knowledge that E2 has important physiological roles in men has clinical applications. Firstly, standard therapy in hypogonadal men should be replacement with T (175), and not with non-aromatizable androgens, selective androgen receptor modulators or AIs to enhance endogenous testosterone production. These latter approaches do not correct the deficiency of estrogen action. Moreover, AIs require hypothalamic–pituitary responsiveness and are not effective in secondary organic hypogonadism or indeed in primary organic hypogonadism where circulating gonadotrophins are already high. In a 12-month RCT of AI therapy in older symptomatic men with low serum testosterone, BMD declined in those treated with AI despite increases in serum testosterone (102). Similar negative effects on BMD have been shown with DHT (32). AIs do have off-label clinical roles in boys with aromatase excess syndrome, precocious puberty due to testotoxicosis, and possibly idiopathic short stature, in which cases they appear to improve adult height (176). AIs and antiestrogens are also clinically useful in boys and men with gynecomastia due to E2 excess (177). However, concerns over skeletal safety of AIs in boys and men remain (176).

The clinical utility of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) in middle aged and older men with low testosterone is also under investigation (reviewed in (178)). Like AIs, SERMs can enhance endogenous testosterone production in men with preserved hypothalamic–pituitary responsiveness, but, in contrast to AIs, have some ER agonistic activity in somatic tissues such as the skeleton. Clinical trials to date however have been relatively small, short term and have not been designed to provide definitive evidence for clinical use (178). Furthermore, limited data suggest that the SERM, raloxifene, is an inadequate substitute for E2 when skeletal maturity has not yet been attained. Unlike subsequent transdermal E2 treatment, 12 months of raloxifene proved ineffective in fusing epiphyses in a young man with congenital aromatase deficiency (179). Forearm BMD improved in association with raloxifene treatment, but bone age did not advance.

Secondly, there are potential roles for E2 treatment in men requiring ADT for prostate cancer currently under investigation, either in the form of high-dose transdermal E2 as the method of achieving medical castration or as low-dose transdermal add-back to mitigate vasomotor symptoms and bone and metabolic side effects of GnRH analog therapy (170). Some clinical evidence already suggests E2 therapy is effective for vasomotor symptoms in men undergoing such therapy (180).

Thirdly, measurement of serum E2 concentration in the clinic, ideally with mass spectrometry, is useful in the evaluation of possible E2 excess (177, 181) and in differentiating the rare causes of deficient E2 action leading to persistent linear growth, delayed bone age and osteoporosis. This differential includes estrogen resistance, aromatase deficiency and rare combined defects of steroid synthesis (182).

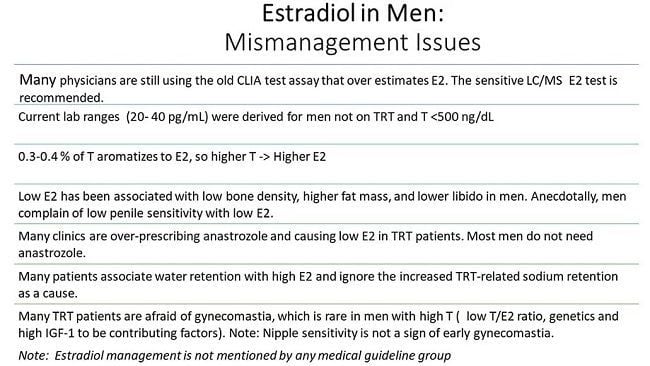

At present, serum E2 measurement should not be part of the routine evaluation of clinical conditions such as hypogonadism or osteoporosis because there is no evidence that E2 measurements provide clinically actionable information beyond that of circulating testosterone. Access to validated gold standard mass spectrometry E2 measurement techniques for routine clinical use is still limited for many clinicians, and measurement by immunoassay is highly inaccurate and tends to overestimate E2 at the low serum concentrations present in men (183). Even if circulating E2 can be accurately measured, because E2 in men is produced locally and diffusely in aromatase-containing tissues, and acts in a paracrine fashion, it is unclear to what extent serum E2 concentrations reflect sufficiency of estrogenic effects in any particular tissue. Serum E2 thresholds establishing sufficiency of estrogen action in various tissues have been proposed (170). Clearly however, given the importance of E2 in male health, further studies, using increasingly available mass spectrometry assays, are needed to define the utility of serum E2 measurements in clinical practice.

Conclusion

Recent evidence has demonstrated that many biological actions historically attributed to testosterone are instead, at least in part, mediated by its aromatization product E2. The data are strongest for effects on bone, fat mass, insulin resistance and VMS. The relevance of these data is that clinically efficacious treatment of male hypogonadism is best achieved with testosterone, which provides ‘three hormones in one’ – testosterone, DHT, E2. Conversely, this evidence raises caution regarding the use of selective androgen receptor modulators, non-aromatizable androgens and AIs for male hypogonadism, and emphasizes the need for better understanding of the tissue-specific effects of SERMs, which are also used off label by some practitioners for this purpose. They also suggest that E2, either as sole ADT or as add-back to conventional GnRH analog-based ADT, may be a promising treatment to mitigate some of the adverse effects of ADT given to men with prostate cancer. Most current studies in men are relatively small, short term, and the design of experimental studies does not always recapitulate physiology. More research is needed to better understand the relative roles of testosterone versus E2 in somatic and reproductive studies and to dissect the relative biologic roles of circulating versus locally produced E2.

MECHANISMS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY

Estradiol as a male hormone

Nicholas Russell and Mathis Grossmann

Abstract

Evidence has been accumulating that, in men, some of the biological actions traditionally attributed to testosterone acting via the androgen receptor may in fact be dependent on its aromatization to estradiol (E2). In men, E2 circulates at concentrations exceeding those of postmenopausal women, and estrogen receptors are expressed in many male reproductive and somatic tissues. Human studies contributing evidence for the role of E2 in men comprise rare case reports of men lacking aromatase or a functional estrogen receptor alpha, short-term experiments manipulating sex steroid milieu in healthy men, men with organic hypogonadism or men with prostate cancer treated with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and from observational studies in community-dwelling men. The collective evidence suggests that, in men, E2 is an important hormone for hypothalamic–pituitary–testicular axis regulation, reproductive function, growth hormone insulin-like growth factor-1 axis regulation, bone growth and maintenance of skeletal health, body composition and glucose metabolism and vasomotor stability. In other tissues, particularly brain, elucidation of the clinical relevance of E2 actions requires further research. From a clinical perspective, the current evidence supports the use of testosterone as the treatment of choice in male hypogonadism, rather than aromatase inhibitors (which raise testosterone and lower E2), selective androgen receptor modulators and selective estrogen receptor modulators (with insufficiently understood tissue-specific estrogenic effects). Finally, E2 treatment, either as add-back to conventional ADT or as sole mode of ADT could be a useful strategy for men with prostate cancer.

Introduction

Estrogens were demonstrated in the urine of men in the 1920s (1) and in the testis in 1952 (2). In 1937 Steinach and Kun demonstrated that administration of large doses of testosterone to men increased the estrogenic activity of their urine and inferred in vivo conversion of testosterone to estrogens (3). Subsequent advances included the identification, isolation, sequencing and regulatory characterization of the aromatase cytochrome P450 enzyme, product of the CYP19A1 gene, the enzyme responsible for aromatization of testosterone to 17β estradiol (E2) and androstenedione to estrone (E1), the major endogenous estrogens (4). Many other non-aromatized endogenous steroids, estrogen metabolites and environmental and pharmaceutical compounds with diverse structures have minor estrogenic activity (5, 6).

Physiology and metabolism of estrogens

Circulating E2 in men

One quarter to one half of circulating E2 is estimated to originate from direct testicular secretion, with the rest resulting from peripheral aromatization of testosterone, particularly in adipose tissue, muscle, bone and brain (7, 8, 9). Median serum E2 concentrations are around 150 pmol/L in healthy young men and 90 pmol/L in healthy older men, compared to 400 pmol/L in premenopausal women, while healthy male circulating testosterone concentrations are substantially higher, ranging from about 10 to 30 nmol/L, although these concentrations vary across studies performed in different populations and using different assay methodologies (10, 11).

Metabolism of estrogens

The predominant metabolic pathway for E2, the most potent endogenous estrogen, is reversible oxidation to E1 by the widely distributed 17β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (12). For infusions of labeled steroid, oxidation of E2 to E1 is more rapid than the reductive reaction (13). E2 and E1, the parent estrogens, undergo irreversible hydroxylation at the 2-, 4- or 16-carbon positions by cytochrome P450 enzymes, particularly CYP1A2 and CYP3A4, located in the liver and other tissues (14). The 4-hydroxy-estrogens are similar in potency to the parent estrogens, while the 2-hydroxy-estrogens are less potent and therefore, because they retain ER-binding affinity, may be relatively anti-estrogenic (15). The 2- and 4-hydroxylated metabolites undergo methylation to less active forms (16). The 16α hydroxyestrogens, including estriol (E3), retain minor estrogenic activity (17).

Estrogen receptors in men

ERα and ERβ, encoded by the ESR1 and ESR2 genes respectively, are members of the nuclear receptor superfamily. Multiple isoforms of each receptor type exist, created by differential splicing of exons (19). More recently, the transmembrane G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER) was identified (20). ERs are expressed throughout the human male reproductive tract, and also in male brain, cardiovascular system, liver, bone, adipose tissue, pancreatic islets and skeletal muscle (21).

Intracrinology of estrogens

Most clinical studies infer biological actions from serum E2 concentrations, based on the classical endocrine concept that gonadal-produced sex steroids circulate to target tissues to exert their effects. These studies do not take into account cellular uptake, either after dissociation from SHBG or albumin or perhaps as an SHBG-bound complex (24), nor local production and metabolism of sex steroids in target tissues themselves, with potential for autocrine and paracrine actions. As reviewed elsewhere (25), some extragonadal tissues possess the capacity for de novo sex steroid synthesis and/or for metabolism of circulating precursors, such as adrenal produced dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, and express steroidogenic enzymes not reported to be active in gonadal tissues. The net biologic effects of such locally acting estrogenic compounds in individual target tissues are not known but, in combination with the use of inaccurate immunoassays, may contribute to the relatively modest associations of circulating E2 concentrations with biologic phenotypes reported in many clinical studies.

Hypothalamic–pituitary–testicular axis regulation

Overall, human studies suggest that E2-mediated negative feedback on gonadotropin activation involves both hypothalamic and pituitary actions. Moreover, while E2 is important for this negative feedback, it is likely that AR-mediated effects also play a role.

Reproduction

Spermatogenesis

A comprehensive discussion of the role of E2 in testicular function and spermatogenesis is beyond the scope of this manuscript and recent reviews exist (21). Briefly, ERα and ERβ are expressed throughout the human male reproductive tract, including in germ cells, although there are conflicting data in certain cell types. Aromatase is found in human immature germ cells, spermatozoa, efferent ductules of the testis and epididymis (21). While studies in mice have demonstrated important roles for estrogen signaling in male fertility, studies in men have been less dramatic and less conclusive.

Libido and erectile function

The evidence from men with congenital non-functional ERα or aromatase deficiency suggests that E2 is not essential for male libido and erectile function (39, 46), but various lines of evidence support some physiological role. In non-blinded studies, two men with aromatase deficiency had increments in libido and sexual activity during E2 treatment, either alone (51) or with testosterone (47). Non-definitive evidence from men with prostate cancer suggests that androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) using estrogens may better maintain sexual function than surgical castration (52) and GnRH analogs (53).

Prostate

Estrogens are synthesized by aromatase in the prostate stroma (55) and have autocrine and paracrine actions. ERα appears to be primarily located in prostate stromal cells while ERβ is found primarily in the epithelium (56). GPER has been demonstrated in stromal cells and epithelial progenitor cells (57). Estrogens appear to have a role during normal prostate development in utero, a time of high systemic estrogen exposure (56, 57). However, unphysiologically timed or dosed estrogen exposure during prostate gland development influences later prostate cancer risk in animal models (58).

In summary, the collective evidence from rare case studies (including ER and aromatase-deficient men) and experimental studies in healthy younger and older men is consistent with the fact that ER signaling plays a role in various aspects of male reproductive health, including testicular descent, spermatogenesis and sexual function. ER signaling also has complex effects on the prostate gland, but the consequences for prostate health and disease are poorly understood.

Growth hormone insulin-like growth factor-1 axis

Men with congenital aromatase deficiency have impaired stimulated growth hormone (GH) secretion and low insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) (66). Exogenous E2 in these men was not able to normalize GH secretion (66), possibly because of abnormal development of the GH–IGF-1 axis in the setting of congenital E2 deficiency or because restoration of normal circulating E2 concentration is insufficient if local E2 production remains impaired (67). Additional lines of evidence from preclinical models, women, and indirect evidence from men, suggest that E2 is important in regulation of GH secretion by both direct and indirect mechanisms (67, 68).

In summary, E2 rather than testosterone appears the main sex steroid regulator of the GH-IGF-1 axis in men.

Bone

Osteoblasts, osteocytes, osteoclasts and marrow stromal cells contain ER and AR (72, 73). The weight of evidence points to E2, acting via ERα, as the predominant sex steroid in the development and maintenance of the male skeleton (74). Androgens have a smaller but important role, particularly in promoting periosteal apposition to increase bone size in men.

E2, linear bone growth, cessation of growth and achievement of peak bone mass

E2 has concentration-dependent effects on skeletal growth. Pre-puberty, serum and tissue E2 is extremely low, and skeletal growth, more appendicular than axial, is mediated by the GH–IGF-1 axis (76). Skeletal sexual dimorphism does not arise until puberty (77). Men are taller than women, predominantly because of a longer period of prepubertal growth, leading to longer leg length (78).

E2 and bone loss in older men and in models of hypogonadism

Severe hypogonadism in older men induces accelerated bone remodeling and deterioration in bone density and microarchitecture (91). Observational and experimental evidence suggests that these effects are mostly E2 dependent.

Serum E2 and fractures in men

In summary, the available data suggest that, while testosterone has direct effects on bone remodeling and bone microstructure, and indirect effects though anabolic effects on skeletal muscle, E2 appears to be the sex steroid predominantly important for skeletal health in men.

Body composition and glucose and lipid metabolism

Body composition: E2, muscle and fat

In men, aromatase activity is reported in skeletal muscle (114) and adipose tissue (9). Aromatase is strongly expressed in the stroma of human adipose tissue, although nearly all of these data are from women (115). ERs are also expressed in human adipose tissue (116) and there is low level expression of ERα in human skeletal muscle (117).

Effects of obesity on E2

Observational studies have consistently found a negative linear correlation between serum testosterone and body mass index in men (125). Insulin resistance lowers SHBG and therefore total testosterone, but as obesity increases, free testosterone also falls, and this is associated with low or inappropriately normal LH. One hypothesized mechanism is that in obesity, excess adipose tissue aromatase activity elevates E2 concentrations, which increases negative feedback on LH production. In the 1970s higher E1 and E2 serum concentrations and urinary production rates were reported in obese men compared with lean controls (126). However, there are little subsequent data to support the excess aromatization hypothesis. For example, a study by Dhindsa et al. employed mass spectrometry and equilibrium dialysis to accurately measure total and free E2 in obese men with type 2 diabetes with either subnormal or normal serum free T (127). Men with subnormal free testosterone had lower E2 concentrations than those with normal serum free testosterone. In Dhindsa’s study, and also in the European Male Aging Study in which men mostly did not have diabetes (128), testosterone and E2 concentrations were positively correlated.

Glucose metabolism

Subnormal serum testosterone is prevalent in men with type 2 diabetes. Contrary to the hypothesis that this low testosterone is due to negative feedback from elevated serum E2 produced by excessive adipose tissue aromatase, Dhindsa et al. showed that E2 in men with type 2 diabetes is low and remains directly correlated with serum testosterone (127)

Lipid metabolism

Roelfsema et al. performed a short-term clamp study to isolate the effect of physiological E2 concentration on lipids and inflammatory markers in healthy older men (140). This design avoided confounding effects of changes in body composition and physical activity. Over 3 weeks, 74 men were rendered acutely hypogonadal by a GnRH antagonist followed by randomization to IM testosterone add-back or placebo, AI or placebo, and transdermal E2 patch or no patch. Four groups were analyzed: IM placebo (T−E2−); IM T plus oral placebo (T+E2+); IM T plus oral AI (T+E2−) and IM T plus AI plus E2 patch (T+E2++). Mean serum testosterone concentrations were 14.9–17.3 nmol/L at baseline. The intervention produced testosterone concentrations of 5.7 nmol/L in the testosterone-E2 group, different from the 25.9 to 29.3 nmol/L in the three groups receiving testosterone add-back. Mean serum E2 concentrations were 77–99 pmol/L at baseline, then 4 pmol/L in the testosterone+E2− group, 35 pmol/L in testosterone−E2− group, 115 pmol/L in the T+E2+ group and 301 pmol/L in the T+/E2++ group. Despite an 80-fold range of serum E2 concentrations encompassing the physiological range, linear regression analysis showed that TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, lipoprotein (a) and apolipoprotein B were unrelated to serum E2 or testosterone concentrations. While larger studies are needed to confirm these findings, they suggest that the lipid changes observed in other studies might be due to body composition or activity changes, pharmacological rather than physiological actions or other confounders.

Vascular reactivity and atherosclerotic plaque

In summary, the data suggest that the metabolically beneficial effects of testosterone on body composition are mediated via aromatization of E2 to limit adiposity, including VAT, but that the anabolic effects of testosterone on muscle mass are largely a direct effect via AR signaling. With respect to sex steroid-mediated beneficial effects on insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism, experiments in male rodents and men indicate that these are, at least in part, mediated via E2 signaling in multiple metabolically active tissues. Inferences on effects on lipids and atherosclerosis are limited due to the lack of appropriately designed studies.

Brain

Antenatal effects on brain structure and gender-related behavior

Brain structure and physiology, and resultant cognition and behavior, are sexually dimorphic. The greatest distinctions pertain to structures and behaviors relevant to reproduction. These differences are attributable to differences in gonadal hormone secretion, and the effects of sex chromosome-encoded genes (144, 145, 146).

Cognition

In summary, while E2, acting locally, is critical for brain masculinization during development in rodents, in men, brain masculinization appears to track more closely with testosterone signaling via the AR, although data are limited. Whether sex steroids have effects on cognition is not clear.

Vasomotor stability

The profound sex steroid deficiency induced by ADT with GnRH analogs produces vasomotor symptoms (VMS) in the majority of men (155). In men, as in perimenopausal women, E2 withdrawal is the mediator of this effect. In women E2 withdrawal has been shown to cause release of hypothalamic neurokinin B, a paracrine regulator of heat dissipation effectors (156). In Finkelstein’s paradigm of experimental testosterone and E2 depletion in young men with differential add-back of testosterone with or without AI, men receiving AI had a greater incidence of VMS, and even supraphysiologic serum testosterone concentrations were unable to prevent hot flushes if serum E2 remained <37 pmol/L (157). In a preliminary report of an ongoing RCT comparing two modes of ADT for prostate cancer, high-dose transdermal E2 versus standard GnRH analog therapy, men in the E2 arm had a lower incidence of hot flushes at 6 months (8 vs 46%) (53). Finally, in a 4-week RCT, low-dose transdermal E2 add-back in men receiving GnRH analog therapy, reduced hot flush frequency-severity scores (104).

Effects of excess E2 in men

Excess exposure to estrogens in men can cause gynecomastia, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, and, if the exposure is pre-pubertal, premature epiphyseal closure leading to short stature. This phenotype occurs in the rare, autosomal dominant, aromatase excess syndrome that results from subchromosomal rearrangements that enhance aromatase transcription. (158). The first rearrangements were described in 2003 (159) but cases of familial gynecomastia, likely due to this syndrome have been noted since antiquity (160).

Gynecomastia is the most consistent effect of excess exposure to estrogens in boys and men. In addition to the aromatase excess syndrome, gynecomastia has been described in cases of estrogen-secreting testicular tumors (161) and Sertoli cell proliferation in Peutz Jegher Syndrome (162), excess aromatase expression by hepatocellular carcinoma (163), occupational exposures, abuse of aromatizable androgenic steroids and intentional pharmacological use of estrogens including in transgender women and in men with prostate cancer (164). Gynecomastia is also seen without absolute estrogen excess. Male breast tissue expresses both ER and AR. In females, estrogens stimulate breast tissue, whereas androgens inhibit it (165). This understanding has been extrapolated to men (166). Gynecomastia can occur in circumstances where there is absolute androgen deficiency or where the ratio of circulating free testosterone to free E2 is reduced (164). Examples of the latter include conditions in which SHBG is increased such as thyrotoxicosis or aging (because SHBG binds testosterone more avidly than E2, SHBG elevation reduces free testosterone more than it does free E2) (167).

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals

The Endocrine Society defines an endocrine-disrupting chemical (EDC) as an ‘exogenous chemical or mixture of chemicals, that interferes with any aspect of hormone action’ (171). Many EDCs, such as bisphenol A, p,p′-dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT, now banned), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs, now banned) bind to and activate ERs. Pre- and perinatal exposure to some of these EDCs, and others, have obesogenic, diabetogenic and reproductive effects in rodent studies and there is epidemiological evidence to support similar effects in humans (6). However, causation in humans has not been proven and EDCs can act through diverse mechanisms, including inhibition of androgen production and action, and direct toxic effects on endocrine and reproductive tissues. Therefore, it is impossible at present to isolate particular estrogenic effects of particular EDCs that are responsible for any particular clinical effect in men.

Tissues in which androgen action is independent of aromatization

In certain tissues, AR-mediated actions are clearly predominant. The in utero development of male external genitalia is AR mediated. Micropenis and hypospadias can occur in XY male infants with partial androgen insensitivity syndrome, and topical DHT, which is not aromatized, can produce penile growth (172). The higher male reference range for hemoglobin reflects the impact of androgen action on erythropoiesis. The mechanisms appear to be via AR-mediated reduction in hepatic hepcidin production, thus increasing iron availability for red cell production (173). Male-pattern body hair growth is also AR mediated, illustrated by the efficacy of 5α-reductase inhibitors for treating androgenic alopecia (174).

Clinical implications of E2 physiology in men

Knowledge that E2 has important physiological roles in men has clinical applications. Firstly, standard therapy in hypogonadal men should be replacement with T (175), and not with non-aromatizable androgens, selective androgen receptor modulators or AIs to enhance endogenous testosterone production. These latter approaches do not correct the deficiency of estrogen action. Moreover, AIs require hypothalamic–pituitary responsiveness and are not effective in secondary organic hypogonadism or indeed in primary organic hypogonadism where circulating gonadotrophins are already high. In a 12-month RCT of AI therapy in older symptomatic men with low serum testosterone, BMD declined in those treated with AI despite increases in serum testosterone (102). Similar negative effects on BMD have been shown with DHT (32). AIs do have off-label clinical roles in boys with aromatase excess syndrome, precocious puberty due to testotoxicosis, and possibly idiopathic short stature, in which cases they appear to improve adult height (176). AIs and antiestrogens are also clinically useful in boys and men with gynecomastia due to E2 excess (177). However, concerns over skeletal safety of AIs in boys and men remain (176).

The clinical utility of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) in middle aged and older men with low testosterone is also under investigation (reviewed in (178)). Like AIs, SERMs can enhance endogenous testosterone production in men with preserved hypothalamic–pituitary responsiveness, but, in contrast to AIs, have some ER agonistic activity in somatic tissues such as the skeleton. Clinical trials to date however have been relatively small, short term and have not been designed to provide definitive evidence for clinical use (178). Furthermore, limited data suggest that the SERM, raloxifene, is an inadequate substitute for E2 when skeletal maturity has not yet been attained. Unlike subsequent transdermal E2 treatment, 12 months of raloxifene proved ineffective in fusing epiphyses in a young man with congenital aromatase deficiency (179). Forearm BMD improved in association with raloxifene treatment, but bone age did not advance.

Secondly, there are potential roles for E2 treatment in men requiring ADT for prostate cancer currently under investigation, either in the form of high-dose transdermal E2 as the method of achieving medical castration or as low-dose transdermal add-back to mitigate vasomotor symptoms and bone and metabolic side effects of GnRH analog therapy (170). Some clinical evidence already suggests E2 therapy is effective for vasomotor symptoms in men undergoing such therapy (180).

Thirdly, measurement of serum E2 concentration in the clinic, ideally with mass spectrometry, is useful in the evaluation of possible E2 excess (177, 181) and in differentiating the rare causes of deficient E2 action leading to persistent linear growth, delayed bone age and osteoporosis. This differential includes estrogen resistance, aromatase deficiency and rare combined defects of steroid synthesis (182).

At present, serum E2 measurement should not be part of the routine evaluation of clinical conditions such as hypogonadism or osteoporosis because there is no evidence that E2 measurements provide clinically actionable information beyond that of circulating testosterone. Access to validated gold standard mass spectrometry E2 measurement techniques for routine clinical use is still limited for many clinicians, and measurement by immunoassay is highly inaccurate and tends to overestimate E2 at the low serum concentrations present in men (183). Even if circulating E2 can be accurately measured, because E2 in men is produced locally and diffusely in aromatase-containing tissues, and acts in a paracrine fashion, it is unclear to what extent serum E2 concentrations reflect sufficiency of estrogenic effects in any particular tissue. Serum E2 thresholds establishing sufficiency of estrogen action in various tissues have been proposed (170). Clearly however, given the importance of E2 in male health, further studies, using increasingly available mass spectrometry assays, are needed to define the utility of serum E2 measurements in clinical practice.

Conclusion

Recent evidence has demonstrated that many biological actions historically attributed to testosterone are instead, at least in part, mediated by its aromatization product E2. The data are strongest for effects on bone, fat mass, insulin resistance and VMS. The relevance of these data is that clinically efficacious treatment of male hypogonadism is best achieved with testosterone, which provides ‘three hormones in one’ – testosterone, DHT, E2. Conversely, this evidence raises caution regarding the use of selective androgen receptor modulators, non-aromatizable androgens and AIs for male hypogonadism, and emphasizes the need for better understanding of the tissue-specific effects of SERMs, which are also used off label by some practitioners for this purpose. They also suggest that E2, either as sole ADT or as add-back to conventional GnRH analog-based ADT, may be a promising treatment to mitigate some of the adverse effects of ADT given to men with prostate cancer. Most current studies in men are relatively small, short term, and the design of experimental studies does not always recapitulate physiology. More research is needed to better understand the relative roles of testosterone versus E2 in somatic and reproductive studies and to dissect the relative biologic roles of circulating versus locally produced E2.

Attachments

Last edited by a moderator: