Nelson Vergel

Founder, ExcelMale.com

Clomiphene-Associated Suicide Behavior in a Man Treated for Hypogonadism: Case Report and Review of The Literature

Introduction

Of couples with infertility issues, half are caused by male infertility problems, and as much as 50% of these infertile men are diagnosed with idiopathic infertility. Despite how frequently idiopathic infertility is diagnosed in men, the treatment for this condition is quite controversial, and up to two-thirds of providers use off-label medical therapies.1 Of these therapies, clomiphene is one of the most commonly used, along with hCG and anastrozole.1 A survey investigating urology practice patterns reported that approximately 90% of respondents who used empirical (non–Food and Drug Administration approved) medical therapy for idiopathic male infertility prescribed clomiphene. Despite the rising use of clomiphene for idiopathic male infertility, the overall prescribing practices in the United States and worldwide are not well defined.1

Clomiphene is a selective estrogen receptor modulator that affects the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal axis and indirectly increases luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone release. These hormone level elevations lead to increased serum testosterone levels and spermatogenesis in men. Clomiphene is Food and Drug Administration indicated for female factor infertility/ovulation induction; however, research to date on its effectiveness in men is equivocal.2 Although several studies indicate improvements in hormonal parameters in men, there have also been studies that show no clinically significant difference in outcomes such as semen quality or pregnancy rates.2 and 3

Because clomiphene is a relatively new and off-label treatment for male infertility, most of the data available on unfavorable psychiatry outcomes come from small studies or case reports of women only. To date, there have been 8 case reports of severe psychiatric manifestations with clomiphene use in women. These cases have often required psychiatric hospitalization with symptoms including anxiety, insomnia, thought disorganization, and delusions of reference. Most of these case reports are consistent with psychosis, including some form of delusions, hallucinations, or thought disorder4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10; however, 1 report describes manic delirium.11 Other documented psychologic side effects of clomiphene in women include irritability and mood swings.12 and 13 Although studies within gynecological patient populations are limited and small-scale, the available data suggest that women treated with clomiphene for infertility have high rates (>70%) of psychologic side effects including mood swings, feeling down, anxiety, and irritability.13

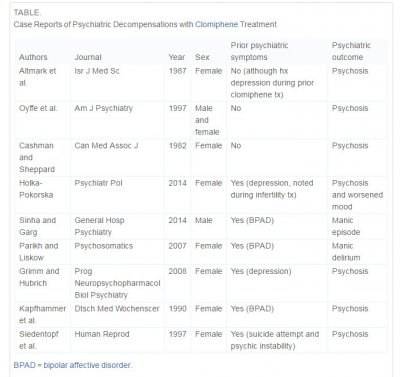

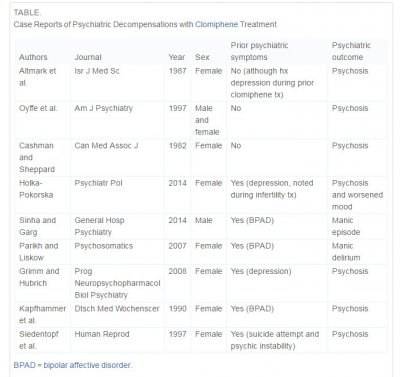

Literature on the negative psychiatric side effects of clomiphene in men is limited to 2 case reports, one of which describes a psychotic episode5 and the other a manic episode.14 Ours is the first to describe a temporal relationship between clomiphene infertility treatment and a severe depressive episode with a suicide attempt. Many of the case reports discussed earlier indicate a known psychiatric history; however, some do not (see Table). In those case reports that do not describe a history of mental illness, it is possible that a remote prior episode or subclinical psychiatric issue went unreported. For many patients, a history of mental illness can be subtle if not exhaustively explored, such as the history of prior suicide attempt and lifetime “psychic instability” described in the 1997 case report by Siedentopf et al.9

Case Report

Mr. M, a 39-year-old man, with a self-reported history of depression was recently started on clomiphene (Clomid) therapy for management of infertility and was admitted following a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the left chest (with a 12-gauge shotgun). He was initially resuscitated and stabilized at another hospital; a left chest tube was placed, and he was intubated for airway protection and was transferred via aircraft to our hospital. On arrival in the emergency department, he was found to be in stage 2 hypovolemic shock. After initial resuscitation, he was taken for a computed tomographic scan that showed multiple shotgun pellets in his chest and abdominal cavity. He was taken to the operating room emergently for exploratory laparotomy, and a colonic serosal injury was repaired.

He was managed briefly in the intensive care unit and stabilized. He was extubated on postoperative day 3. He was treated conservatively with oxygen supplementation and pulmonary toilet. However, he developed left upper extremity weakness secondary to neuropraxia from the dissipation force generated by the gunshot blast. This was evaluated by the Neurology and Physical Therapy services with recommendations for the management of his symptoms. Psychiatry consultation was requested for suicide risk assessment and management of depression.

Mr. M initially endorsed shame, guilt, and feeling overwhelmed by recent events but also expressed feeling thankful that he was alive. He reported prior episodes of mild-to-moderate depression that responded well to sertraline. Seven months before admission, Mr. M was started on clomiphene therapy at a dose of 50 mg daily for treatment of hypogonadism of unknown etiology and infertility. Before starting clomiphene therapy, his thyroid stimulating hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, prolactin, estradiol, and testosterone levels were within the reference range. Because his pre-clomiphene testosterone level was in the low reference range (i.e., 140.5 ng/dL), clomiphene therapy was started. A subsequent testosterone level was 352 ng/dL and a follow-up level 10 weeks later, 17 weeks before his suicide attempt, was reported as “stable” at 347 ng/dL. As his mood was thought to be stable at the time he began clomiphene therapy, he stopped sertraline therapy under physician guidance. He had a history of discontinuing sertraline several times in the past when feeling well and was without any history of suicidal ideation during these periods. As per Mr. Mʼs report, his primary care physician recommended discontinuing sertraline this time because clomiphene alone “should be helpful for my mood.” Mr. M reported mood changes within a month of starting clomiphene therapy, and he developed suicidal ideation within 2 months. He stated that he bought a shotgun 2 months after beginning clomiphene therapy with the intent to use it to end his life. Mr. M reported that his suicidal ideation persisted and intensified from this point on. Other depressive symptoms over this time included depressed mood, increased appetite, insomnia, fatigue, and decreased concentration. Mr. Mʼs fiancée noticed that he was more withdrawn, with decreased motivation; however, she did not suspect or anticipate any suicidality nor did she have knowledge of the shotgun he acquired.

In the months preceding his suicide attempt, he had several brief episodes of intense, intrusive, and obsessive thoughts focused on suicide. Mr. M did not report or exhibit any psychotic symptoms on examination. In describing his suicide attempt, he reported that he went to an isolated area of the countryside and walked along an abandoned railroad track before pulling the trigger. Immediately after he shot himself, he called 911 so his family would know what happened to him (he did not tell anyone his intentions or leave a suicide note). He cited no specific emotional trigger for his suicide attempt; rather that he was no longer able to come up with a reason to continue living. He had no history of prior suicide attempts or history of parasuicidal behaviors.

Clomiphene therapy was stopped on hospital admission. Two days after clomiphene discontinuation, Mr. M described a feeling of “the fog being lifted,” as he no longer felt consumed by his depression and frequent obsessive suicidal thoughts. Coinciding with his stabilized respiratory status, his mood continued to improve and he consistently showed a full affect without signs or symptoms of depression. The Psychiatry Consultation Service recommended admission to inpatient psychiatry and restarting sertraline given his history of depression and previous good response. Sertraline was restarted 8 days after admission. In light of his initial critical condition and urgent need for air transport, there was no toxicology screen performed for drugs of abuse at the outside hospital or on arrival at our institution. As psychiatry was not consulted until 5 days after admission, and he had no history of substance abuse, there was no indication at that time to perform a toxicology screen.

During his short psychiatric admission, the dose of sertraline was increased to 100 mg/d and outpatient services were coordinated.

Discussion

Although there are several case reports of clomipheneʼs association with either manic or psychotic symptom onset, ours is the first case report to describe a potential exacerbation of underlying depressive illness, with near-fatal consequences. As in previous case reports, the causative association of clomiphene with the exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms cannot be definitively inferred without a rechallenge of clomiphene (which would be unethical). However, given Mr. Mʼs history and the temporal association of both the onset and resolution of his symptoms with clomiphene initiation and discontinuation, respectively, it is reasonable to conclude that this was most likely a case of medication-induced mood disorder. Although it cannot be determined with certainty that clomiphene was solely responsible for his psychiatric decline, use of the Naranjo scale to estimate the probability of clomiphene causing his suicidal behavior results in a score of 5, or that the causative effect was “probable.”15 It is important to consider the potential effect of discontinuing sertraline around the same time that clomiphene was started in this case. However, Mr. Mʼs history of multiple periods off of sertraline without any suicidal ideation, along with the fact that his depressive and suicidal symptoms ended quickly after the discontinuation of clomiphene (days before sertraline was restarted) support the hypothesis that clomiphene was main cause of his suicidal behavior, as opposed to the discontinuation of sertraline.

This case report and others suggest severe (i.e., requiring psychiatric hospitalization) psychiatric presentations associated with clomiphene use. It is imperative to research this area further because significant morbidity and mortality might be avoided if strict screening criteria were implemented, and clomiphene was avoided in patients suspected of being particularly vulnerable to psychologic side effects of this medication. As clomiphene is increasingly used as an off-label treatment of idiopathic hypogonadism in men, further studies in men are needed because previously reported outcomes in women cannot be generalized to male populations.

Potential mechanisms of clomiphene-induced psychiatric symptoms remain elusive, and there has been no clearly defined mechanism of interaction between estrogen/testosterone modulation and mood. Although the exact mechanism that clomiphene influences psychiatric symptoms is unknown, it has primary effects on altering a system that is thought to be a critical component of mood and stress responses, the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. By causing negative feedback of the estrogen receptor, clomiphene indirectly enhances luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone release, which ultimately leads to increased testosterone levels. A possible mechanism of action is through direct effects of increased testosterone levels on androgen receptors in the brain, thereby modulating emotional states. Proposed neurobiological targets include catecholaminergic cells in the hypothalamus and other limbic areas. Perhaps the complexity and heterogeneity within this model accounts for the significant variety of psychiatric symptoms documented in the literature.

Most of the data to date suggest that patients with a history of psychiatric illness may be particularly vulnerable to psychiatric side effects of clomiphene. In addition, the stress and psychologic burden of infertility evaluation and treatment must be considered.16 It is possible that hormonal changes induced by clomiphene, in combination with the psychologic distress of infertility treatment, work in concert to generate psychiatric symptoms, particularly in those with underlying mental illness. Considering this, comprehensive psychiatric screening and appropriate treatment should be implemented for couples undergoing infertility treatment, especially if clomiphene is being considered as a treatment. No medication adverse event was filed with the case presented here; however, this case report as well as the publications reviewed here raises important questions such as whether the potential for psychiatric side effects of clomiphene should be expanded on in the product insert. To date, the only psychiatric adverse events listed for this medication are “increased nervous tension” and “depression.”

Given the compelling evidence reviewed here, at the very least, patients should be informed of the potential for clomiphene to cause de novo psychiatric symptoms or to exacerbate underlying disorders. Future and larger-scale studies would be instrumental in further evaluating the potential dangers of psychiatric complications associated with clomiphene therapy.

Psychosomatics

Volume 56, Issue 5, September–October 2015, Pages 598–602

Introduction

Of couples with infertility issues, half are caused by male infertility problems, and as much as 50% of these infertile men are diagnosed with idiopathic infertility. Despite how frequently idiopathic infertility is diagnosed in men, the treatment for this condition is quite controversial, and up to two-thirds of providers use off-label medical therapies.1 Of these therapies, clomiphene is one of the most commonly used, along with hCG and anastrozole.1 A survey investigating urology practice patterns reported that approximately 90% of respondents who used empirical (non–Food and Drug Administration approved) medical therapy for idiopathic male infertility prescribed clomiphene. Despite the rising use of clomiphene for idiopathic male infertility, the overall prescribing practices in the United States and worldwide are not well defined.1

Clomiphene is a selective estrogen receptor modulator that affects the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal axis and indirectly increases luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone release. These hormone level elevations lead to increased serum testosterone levels and spermatogenesis in men. Clomiphene is Food and Drug Administration indicated for female factor infertility/ovulation induction; however, research to date on its effectiveness in men is equivocal.2 Although several studies indicate improvements in hormonal parameters in men, there have also been studies that show no clinically significant difference in outcomes such as semen quality or pregnancy rates.2 and 3

Because clomiphene is a relatively new and off-label treatment for male infertility, most of the data available on unfavorable psychiatry outcomes come from small studies or case reports of women only. To date, there have been 8 case reports of severe psychiatric manifestations with clomiphene use in women. These cases have often required psychiatric hospitalization with symptoms including anxiety, insomnia, thought disorganization, and delusions of reference. Most of these case reports are consistent with psychosis, including some form of delusions, hallucinations, or thought disorder4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10; however, 1 report describes manic delirium.11 Other documented psychologic side effects of clomiphene in women include irritability and mood swings.12 and 13 Although studies within gynecological patient populations are limited and small-scale, the available data suggest that women treated with clomiphene for infertility have high rates (>70%) of psychologic side effects including mood swings, feeling down, anxiety, and irritability.13

Literature on the negative psychiatric side effects of clomiphene in men is limited to 2 case reports, one of which describes a psychotic episode5 and the other a manic episode.14 Ours is the first to describe a temporal relationship between clomiphene infertility treatment and a severe depressive episode with a suicide attempt. Many of the case reports discussed earlier indicate a known psychiatric history; however, some do not (see Table). In those case reports that do not describe a history of mental illness, it is possible that a remote prior episode or subclinical psychiatric issue went unreported. For many patients, a history of mental illness can be subtle if not exhaustively explored, such as the history of prior suicide attempt and lifetime “psychic instability” described in the 1997 case report by Siedentopf et al.9

Case Report

Mr. M, a 39-year-old man, with a self-reported history of depression was recently started on clomiphene (Clomid) therapy for management of infertility and was admitted following a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the left chest (with a 12-gauge shotgun). He was initially resuscitated and stabilized at another hospital; a left chest tube was placed, and he was intubated for airway protection and was transferred via aircraft to our hospital. On arrival in the emergency department, he was found to be in stage 2 hypovolemic shock. After initial resuscitation, he was taken for a computed tomographic scan that showed multiple shotgun pellets in his chest and abdominal cavity. He was taken to the operating room emergently for exploratory laparotomy, and a colonic serosal injury was repaired.

He was managed briefly in the intensive care unit and stabilized. He was extubated on postoperative day 3. He was treated conservatively with oxygen supplementation and pulmonary toilet. However, he developed left upper extremity weakness secondary to neuropraxia from the dissipation force generated by the gunshot blast. This was evaluated by the Neurology and Physical Therapy services with recommendations for the management of his symptoms. Psychiatry consultation was requested for suicide risk assessment and management of depression.

Mr. M initially endorsed shame, guilt, and feeling overwhelmed by recent events but also expressed feeling thankful that he was alive. He reported prior episodes of mild-to-moderate depression that responded well to sertraline. Seven months before admission, Mr. M was started on clomiphene therapy at a dose of 50 mg daily for treatment of hypogonadism of unknown etiology and infertility. Before starting clomiphene therapy, his thyroid stimulating hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, prolactin, estradiol, and testosterone levels were within the reference range. Because his pre-clomiphene testosterone level was in the low reference range (i.e., 140.5 ng/dL), clomiphene therapy was started. A subsequent testosterone level was 352 ng/dL and a follow-up level 10 weeks later, 17 weeks before his suicide attempt, was reported as “stable” at 347 ng/dL. As his mood was thought to be stable at the time he began clomiphene therapy, he stopped sertraline therapy under physician guidance. He had a history of discontinuing sertraline several times in the past when feeling well and was without any history of suicidal ideation during these periods. As per Mr. Mʼs report, his primary care physician recommended discontinuing sertraline this time because clomiphene alone “should be helpful for my mood.” Mr. M reported mood changes within a month of starting clomiphene therapy, and he developed suicidal ideation within 2 months. He stated that he bought a shotgun 2 months after beginning clomiphene therapy with the intent to use it to end his life. Mr. M reported that his suicidal ideation persisted and intensified from this point on. Other depressive symptoms over this time included depressed mood, increased appetite, insomnia, fatigue, and decreased concentration. Mr. Mʼs fiancée noticed that he was more withdrawn, with decreased motivation; however, she did not suspect or anticipate any suicidality nor did she have knowledge of the shotgun he acquired.

In the months preceding his suicide attempt, he had several brief episodes of intense, intrusive, and obsessive thoughts focused on suicide. Mr. M did not report or exhibit any psychotic symptoms on examination. In describing his suicide attempt, he reported that he went to an isolated area of the countryside and walked along an abandoned railroad track before pulling the trigger. Immediately after he shot himself, he called 911 so his family would know what happened to him (he did not tell anyone his intentions or leave a suicide note). He cited no specific emotional trigger for his suicide attempt; rather that he was no longer able to come up with a reason to continue living. He had no history of prior suicide attempts or history of parasuicidal behaviors.

Clomiphene therapy was stopped on hospital admission. Two days after clomiphene discontinuation, Mr. M described a feeling of “the fog being lifted,” as he no longer felt consumed by his depression and frequent obsessive suicidal thoughts. Coinciding with his stabilized respiratory status, his mood continued to improve and he consistently showed a full affect without signs or symptoms of depression. The Psychiatry Consultation Service recommended admission to inpatient psychiatry and restarting sertraline given his history of depression and previous good response. Sertraline was restarted 8 days after admission. In light of his initial critical condition and urgent need for air transport, there was no toxicology screen performed for drugs of abuse at the outside hospital or on arrival at our institution. As psychiatry was not consulted until 5 days after admission, and he had no history of substance abuse, there was no indication at that time to perform a toxicology screen.

During his short psychiatric admission, the dose of sertraline was increased to 100 mg/d and outpatient services were coordinated.

Discussion

Although there are several case reports of clomipheneʼs association with either manic or psychotic symptom onset, ours is the first case report to describe a potential exacerbation of underlying depressive illness, with near-fatal consequences. As in previous case reports, the causative association of clomiphene with the exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms cannot be definitively inferred without a rechallenge of clomiphene (which would be unethical). However, given Mr. Mʼs history and the temporal association of both the onset and resolution of his symptoms with clomiphene initiation and discontinuation, respectively, it is reasonable to conclude that this was most likely a case of medication-induced mood disorder. Although it cannot be determined with certainty that clomiphene was solely responsible for his psychiatric decline, use of the Naranjo scale to estimate the probability of clomiphene causing his suicidal behavior results in a score of 5, or that the causative effect was “probable.”15 It is important to consider the potential effect of discontinuing sertraline around the same time that clomiphene was started in this case. However, Mr. Mʼs history of multiple periods off of sertraline without any suicidal ideation, along with the fact that his depressive and suicidal symptoms ended quickly after the discontinuation of clomiphene (days before sertraline was restarted) support the hypothesis that clomiphene was main cause of his suicidal behavior, as opposed to the discontinuation of sertraline.

This case report and others suggest severe (i.e., requiring psychiatric hospitalization) psychiatric presentations associated with clomiphene use. It is imperative to research this area further because significant morbidity and mortality might be avoided if strict screening criteria were implemented, and clomiphene was avoided in patients suspected of being particularly vulnerable to psychologic side effects of this medication. As clomiphene is increasingly used as an off-label treatment of idiopathic hypogonadism in men, further studies in men are needed because previously reported outcomes in women cannot be generalized to male populations.

Potential mechanisms of clomiphene-induced psychiatric symptoms remain elusive, and there has been no clearly defined mechanism of interaction between estrogen/testosterone modulation and mood. Although the exact mechanism that clomiphene influences psychiatric symptoms is unknown, it has primary effects on altering a system that is thought to be a critical component of mood and stress responses, the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. By causing negative feedback of the estrogen receptor, clomiphene indirectly enhances luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone release, which ultimately leads to increased testosterone levels. A possible mechanism of action is through direct effects of increased testosterone levels on androgen receptors in the brain, thereby modulating emotional states. Proposed neurobiological targets include catecholaminergic cells in the hypothalamus and other limbic areas. Perhaps the complexity and heterogeneity within this model accounts for the significant variety of psychiatric symptoms documented in the literature.

Most of the data to date suggest that patients with a history of psychiatric illness may be particularly vulnerable to psychiatric side effects of clomiphene. In addition, the stress and psychologic burden of infertility evaluation and treatment must be considered.16 It is possible that hormonal changes induced by clomiphene, in combination with the psychologic distress of infertility treatment, work in concert to generate psychiatric symptoms, particularly in those with underlying mental illness. Considering this, comprehensive psychiatric screening and appropriate treatment should be implemented for couples undergoing infertility treatment, especially if clomiphene is being considered as a treatment. No medication adverse event was filed with the case presented here; however, this case report as well as the publications reviewed here raises important questions such as whether the potential for psychiatric side effects of clomiphene should be expanded on in the product insert. To date, the only psychiatric adverse events listed for this medication are “increased nervous tension” and “depression.”

Given the compelling evidence reviewed here, at the very least, patients should be informed of the potential for clomiphene to cause de novo psychiatric symptoms or to exacerbate underlying disorders. Future and larger-scale studies would be instrumental in further evaluating the potential dangers of psychiatric complications associated with clomiphene therapy.

Psychosomatics

Volume 56, Issue 5, September–October 2015, Pages 598–602