madman

Super Moderator

CASE PRESENTATION

A 64-year-old healthy man presented with prostate cancer diagnosed in 2016. The pathology showed Gleason scores 3+3 and 3+4 in multiple cores and the patient underwent an uncomplicated radical prostatectomy. He regained urinary continence; however, he required injection therapy to restore erectile function

The patient complained of decreased libido and generalized poor performance with his wife, leading to marital distress. Two-morning testosterone levels taken a month apart were 178 ng/ dL and 155 ng/DL (normal range: 300-1100 ng/dL). PSA levels have remained undetectable.

The patient disclosed a long-standing history of hypogonadism (low testosterone [low T]) and said he had been on testosterone supplementation therapy prior to the radical prostatectomy. The testosterone therapy was effective and he expressed interest in restarting replacement treatment.

Other past medical history includes hypothyroidism and high blood pressure.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Genitourinary

• Penis: Normal male phallus with normal urethra. No penile erythema or tenderness. No urethral discharge

• Scrotum: No evidence of scrotal rashes or condylomata

• Testes: Non-tender with no swelling or masses bilaterally. No hernias or varicoceles. Vas deferens and epididymis palpable and normal bilaterally

Relevant Labs

• Testosterone levels (morning, 1 month apart): 178 ng/dL and 155 ng/dL (300-1100 ng/dL)

• Post prostatectomy PSA: undetectable

MANAGEMENT

The risks and benefits of testosterone supplementation post-prostatectomy were discussed with the patient, including the risk of recurrence of his prostate cancer. The patient was started on AndroGel but ultimately switched to injection therapy for more adequate symptom improvement.

COMMENT

Charles Huggins earned a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1966 for his discoveries concerning the hormonal treatment of prostatic cancer. Today, 80 years after his hallmark publication,1 androgen deprivation remains the frontline treatment for advanced prostate cancer. However, the assertion by Huggins and Hodges that testosterone activates prostate cancer has created considerable confusion for urologists who treat hypogonadism. Many urologists still embrace the theory that the administration of testosterone to a man with existing prostate cancer is like “pouring gasoline on a fire.” How are urologists supposed to decide which prostate cancer patients are safe to treat?

First, it is important to answer this question: Do you always need to treat a low T level? Patients are frequently sent to urologists with low T levels but do not show any signs or symptoms of low T such as decreased sex drive and/or erectile dysfunction. I follow the AUA guideline definition of low T: the observation of 2 morning low T values (T level <300 ng/dL) followed by the signs and symptoms of low T (physical, cognitive, or sexual symptoms) prior to initiating testosterone replacement (Table 1).2

The AUA guideline panel’s “Evaluation and Management of Testosterone Deficiency,”2 completed in 2018, guides the management of hypogonadism. The panel developed a list of 31 guideline statements that are intended to help the clinician safely counsel patients with low T levels and treat and follow the condition.

A large percentage of men with prostate cancer, low T levels, and low T symptoms do not receive supplementation because of the potential adverse impact on prostate cancer progression. The AUA guideline panel performed a systematic review that yielded more than 15,000 references, including articles addressing testosterone replacement and prostate cancer for patients on active surveillance or treated via radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy

The panel agreed that testosterone replacement treatment can be considered for men who have undergone radical prostatectomy and who have undetectable PSA levels and favorable pathology (negative margins and no seminal vesicle or lymph node invasion). Patient selection is key, with caution given regarding high-risk patients, as highlighted in one study that showed increasing PSA values in high-risk post-radical prostatectomy men treated with testosterone.3 With regard to radiation therapy, the panel highlighted a study by Balbontin et al.4 that reported that men placed on testosterone after receiving radiation therapy with or without androgen deprivation therapy did not experience greater rates of recurrence or progression. Last, although data are limited for men on active surveillance, Rhoden and Morgentaler5 indicated that these men did not experience any increase in PSA values or incidence of a prostate cancer diagnosis when compared to men not receiving testosterone. The panel concluded that although PSA may rise in response to testosterone therapy, the increase is minimal, in the realm of 0.3 to 0.5 ng/mL, an increase that is often seen in the first month of testosterone supplement therapy.6

AUA Guideline Statements on Low T and Prostate Cancer

Statement 12: PSA should be measured in men over 40 years of age prior to commencement of testosterone therapy to exclude a prostate cancer diagnosis. (Clinical Principle)

Statement 17: Clinicians should inform patients of the absence of evidence linking testosterone therapy to the development of prostate cancer. (Strong Recommendation: Evidence Level: Grade B)

Statement 18: Patients with testosterone deficiency and a history of prostate cancer should be informed that there is inadequate evidence to quantify the risk-benefit ratio of testosterone therapy. (Expert Opinion)

Saturation Model

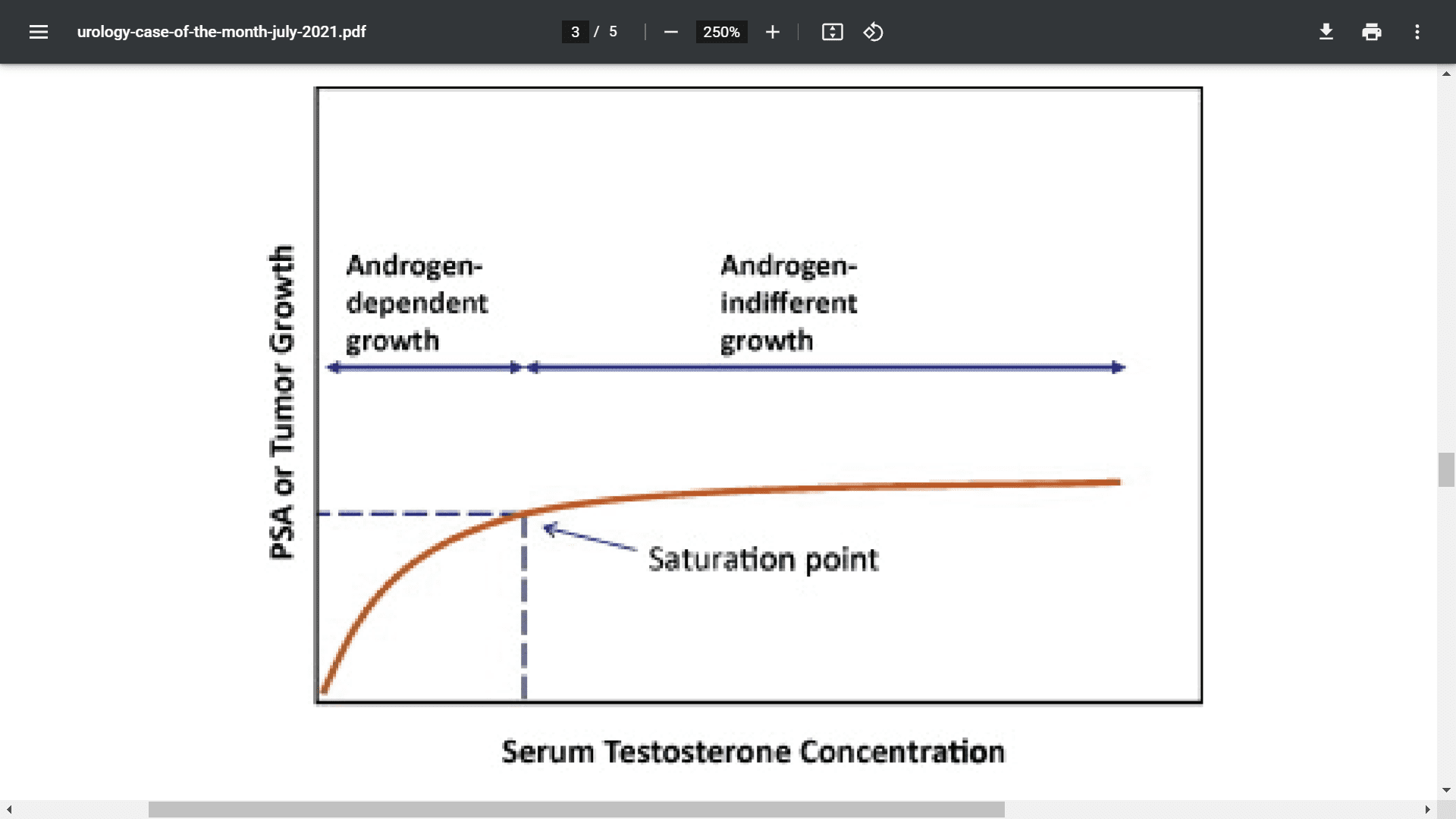

The saturation model, as described by Khera et al.,7 explains the relationship between prostate tissue sensitivity and changes in serum testosterone. The theory is that at low concentrations of androgens, the prostate is very sensitive to changes in androgen levels and PSA will often increase in response to an increase in the concentration. Once the androgen concentration reaches a saturation point, further administration of higher levels of testosterone does not induce any additional androgen-driven changes in prostate tissue growth (Figure 1).7 On the basis of this model, many practitioners who prescribe testosterone for prostate cancer patients feel comfortable knowing the testosterone is most likely not overstimulating prostate tissue.

Figure 1. The saturation model.7 (Source: Reprinted from Khera K, Crawford D, Morales A, et al. A new era of testosterone and prostate cancer: from physiology to clinical implications. Eur Urol. 2014;65[1]:115-123.)

Take-Home Points

Urologists often find themselves between a rock and a hard place when managing symptomatic hypogonadism in men with prostate cancer on active surveillance or after radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy because of the lack of high-level data to appropriately counsel patients on the risks of recurrence or development of new prostate cancer. Many urologists shy away from treating this population for a multitude of reasons, among them medical-legal ramifications and the need for close follow-up with regular testosterone, CBC, and PSA checks. Even further muddying the waters, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration retains a warning regarding the potential risk of prostate cancer in patients who are prescribed testosterone products.

*I continue to follow the AUA guideline of informed decision-making, including having the patient sign a comprehensive consent form that outlines all the potential risks of testosterone supplementation.

A 64-year-old healthy man presented with prostate cancer diagnosed in 2016. The pathology showed Gleason scores 3+3 and 3+4 in multiple cores and the patient underwent an uncomplicated radical prostatectomy. He regained urinary continence; however, he required injection therapy to restore erectile function

The patient complained of decreased libido and generalized poor performance with his wife, leading to marital distress. Two-morning testosterone levels taken a month apart were 178 ng/ dL and 155 ng/DL (normal range: 300-1100 ng/dL). PSA levels have remained undetectable.

The patient disclosed a long-standing history of hypogonadism (low testosterone [low T]) and said he had been on testosterone supplementation therapy prior to the radical prostatectomy. The testosterone therapy was effective and he expressed interest in restarting replacement treatment.

Other past medical history includes hypothyroidism and high blood pressure.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Genitourinary

• Penis: Normal male phallus with normal urethra. No penile erythema or tenderness. No urethral discharge

• Scrotum: No evidence of scrotal rashes or condylomata

• Testes: Non-tender with no swelling or masses bilaterally. No hernias or varicoceles. Vas deferens and epididymis palpable and normal bilaterally

Relevant Labs

• Testosterone levels (morning, 1 month apart): 178 ng/dL and 155 ng/dL (300-1100 ng/dL)

• Post prostatectomy PSA: undetectable

MANAGEMENT

The risks and benefits of testosterone supplementation post-prostatectomy were discussed with the patient, including the risk of recurrence of his prostate cancer. The patient was started on AndroGel but ultimately switched to injection therapy for more adequate symptom improvement.

COMMENT

Charles Huggins earned a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1966 for his discoveries concerning the hormonal treatment of prostatic cancer. Today, 80 years after his hallmark publication,1 androgen deprivation remains the frontline treatment for advanced prostate cancer. However, the assertion by Huggins and Hodges that testosterone activates prostate cancer has created considerable confusion for urologists who treat hypogonadism. Many urologists still embrace the theory that the administration of testosterone to a man with existing prostate cancer is like “pouring gasoline on a fire.” How are urologists supposed to decide which prostate cancer patients are safe to treat?

First, it is important to answer this question: Do you always need to treat a low T level? Patients are frequently sent to urologists with low T levels but do not show any signs or symptoms of low T such as decreased sex drive and/or erectile dysfunction. I follow the AUA guideline definition of low T: the observation of 2 morning low T values (T level <300 ng/dL) followed by the signs and symptoms of low T (physical, cognitive, or sexual symptoms) prior to initiating testosterone replacement (Table 1).2

The AUA guideline panel’s “Evaluation and Management of Testosterone Deficiency,”2 completed in 2018, guides the management of hypogonadism. The panel developed a list of 31 guideline statements that are intended to help the clinician safely counsel patients with low T levels and treat and follow the condition.

A large percentage of men with prostate cancer, low T levels, and low T symptoms do not receive supplementation because of the potential adverse impact on prostate cancer progression. The AUA guideline panel performed a systematic review that yielded more than 15,000 references, including articles addressing testosterone replacement and prostate cancer for patients on active surveillance or treated via radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy

The panel agreed that testosterone replacement treatment can be considered for men who have undergone radical prostatectomy and who have undetectable PSA levels and favorable pathology (negative margins and no seminal vesicle or lymph node invasion). Patient selection is key, with caution given regarding high-risk patients, as highlighted in one study that showed increasing PSA values in high-risk post-radical prostatectomy men treated with testosterone.3 With regard to radiation therapy, the panel highlighted a study by Balbontin et al.4 that reported that men placed on testosterone after receiving radiation therapy with or without androgen deprivation therapy did not experience greater rates of recurrence or progression. Last, although data are limited for men on active surveillance, Rhoden and Morgentaler5 indicated that these men did not experience any increase in PSA values or incidence of a prostate cancer diagnosis when compared to men not receiving testosterone. The panel concluded that although PSA may rise in response to testosterone therapy, the increase is minimal, in the realm of 0.3 to 0.5 ng/mL, an increase that is often seen in the first month of testosterone supplement therapy.6

AUA Guideline Statements on Low T and Prostate Cancer

Statement 12: PSA should be measured in men over 40 years of age prior to commencement of testosterone therapy to exclude a prostate cancer diagnosis. (Clinical Principle)

Statement 17: Clinicians should inform patients of the absence of evidence linking testosterone therapy to the development of prostate cancer. (Strong Recommendation: Evidence Level: Grade B)

Statement 18: Patients with testosterone deficiency and a history of prostate cancer should be informed that there is inadequate evidence to quantify the risk-benefit ratio of testosterone therapy. (Expert Opinion)

Saturation Model

The saturation model, as described by Khera et al.,7 explains the relationship between prostate tissue sensitivity and changes in serum testosterone. The theory is that at low concentrations of androgens, the prostate is very sensitive to changes in androgen levels and PSA will often increase in response to an increase in the concentration. Once the androgen concentration reaches a saturation point, further administration of higher levels of testosterone does not induce any additional androgen-driven changes in prostate tissue growth (Figure 1).7 On the basis of this model, many practitioners who prescribe testosterone for prostate cancer patients feel comfortable knowing the testosterone is most likely not overstimulating prostate tissue.

Figure 1. The saturation model.7 (Source: Reprinted from Khera K, Crawford D, Morales A, et al. A new era of testosterone and prostate cancer: from physiology to clinical implications. Eur Urol. 2014;65[1]:115-123.)

Take-Home Points

Urologists often find themselves between a rock and a hard place when managing symptomatic hypogonadism in men with prostate cancer on active surveillance or after radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy because of the lack of high-level data to appropriately counsel patients on the risks of recurrence or development of new prostate cancer. Many urologists shy away from treating this population for a multitude of reasons, among them medical-legal ramifications and the need for close follow-up with regular testosterone, CBC, and PSA checks. Even further muddying the waters, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration retains a warning regarding the potential risk of prostate cancer in patients who are prescribed testosterone products.

*I continue to follow the AUA guideline of informed decision-making, including having the patient sign a comprehensive consent form that outlines all the potential risks of testosterone supplementation.