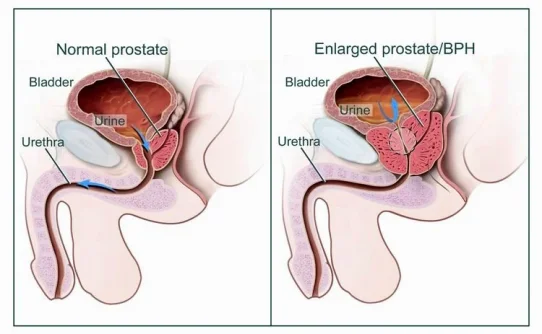

Those who start at low baseline testosterone had the largest PSA increases. That makes sense since low levels of testosterone reduce prostate volume and prostatic specific antigen to levels under the expected median for a specific age. PSA levels normalized after the first month on the gel.

J Urol. 2011 Jul 23. [Epub ahead of print]

Changes in Prostate Specific Antigen in Hypogonadal Men After 12 Months of Testosterone Replacement Therapy: Support for the Prostate Saturation Theory.

Scott Department of Urology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas.

Abstract

PURPOSE:

We measured prostate specific antigen after 12 months of testosterone replacement therapy in hypogonadal men.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Data were collected from the TRiUS (Testim® Registry in the United States), an observational registry of hypogonadal men on testosterone replacement therapy (849). Participants were Testim naïve, had no prostate cancer and received 5 to 10 gm Testim 1% (testosterone gel) daily.

RESULTS:

A total of 451 patients with prostate specific antigen and total testosterone values were divided into group A (197 with total testosterone less than 250 ng/dl) and group B (254 with total testosterone 250 ng/dl or greater). The groups differed significantly in free testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin, but not in age or prostate specific antigen. In group A but not group B prostate specific antigen correlated significantly with total testosterone (r = 0.20, p = 0.005), free testosterone (r = 0.22, p = 0.03) and sex hormone-binding globulin (r = 0.59, p = 0.002) at baseline. After 12 months of testosterone replacement therapy, increase in total testosterone (mean ± SD) was statistically significant in group A (+326 ± 295 ng/dl, p <0.001; final total testosterone 516 ± 28 ng/dl) and group B (+154 ± 217 ng/dl, p <0.001; final total testosterone 513 ± 20 ng/dl). After 12 months of testosterone replacement therapy, increase in prostate specific antigen was statistically significant in group A (+0.19 ± 0.61 ng/ml, p = 0.02; final prostate specific antigen 1.26 ± 0.96 ng/ml) but not in group B (+0.28 ± 1.18 ng/ml, p = 0.06; final prostate specific antigen 1.55 ± 1.72 ng/ml). The average percent prostate specific antigen increase from baseline was higher in group A (21.9%) than in group B (14.1%). Overall the greatest prostate specific antigen was observed after 1 month of treatment and decreased thereafter.

CONCLUSIONS:

Patients with baseline total testosterone less than 250 ng/dl were more likely to have an increased prostate specific antigen after testosterone replacement therapy than those with baseline total testosterone 250 ng/dl or greater, supporting the prostate saturation hypothesis. Clinicians should be aware that severely hypogonadal patients may experience increased prostate specific antigen after testosterone replacement therapy.

J Urol. 2011 Jul 23. [Epub ahead of print]

Changes in Prostate Specific Antigen in Hypogonadal Men After 12 Months of Testosterone Replacement Therapy: Support for the Prostate Saturation Theory.

Scott Department of Urology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas.

Abstract

PURPOSE:

We measured prostate specific antigen after 12 months of testosterone replacement therapy in hypogonadal men.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Data were collected from the TRiUS (Testim® Registry in the United States), an observational registry of hypogonadal men on testosterone replacement therapy (849). Participants were Testim naïve, had no prostate cancer and received 5 to 10 gm Testim 1% (testosterone gel) daily.

RESULTS:

A total of 451 patients with prostate specific antigen and total testosterone values were divided into group A (197 with total testosterone less than 250 ng/dl) and group B (254 with total testosterone 250 ng/dl or greater). The groups differed significantly in free testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin, but not in age or prostate specific antigen. In group A but not group B prostate specific antigen correlated significantly with total testosterone (r = 0.20, p = 0.005), free testosterone (r = 0.22, p = 0.03) and sex hormone-binding globulin (r = 0.59, p = 0.002) at baseline. After 12 months of testosterone replacement therapy, increase in total testosterone (mean ± SD) was statistically significant in group A (+326 ± 295 ng/dl, p <0.001; final total testosterone 516 ± 28 ng/dl) and group B (+154 ± 217 ng/dl, p <0.001; final total testosterone 513 ± 20 ng/dl). After 12 months of testosterone replacement therapy, increase in prostate specific antigen was statistically significant in group A (+0.19 ± 0.61 ng/ml, p = 0.02; final prostate specific antigen 1.26 ± 0.96 ng/ml) but not in group B (+0.28 ± 1.18 ng/ml, p = 0.06; final prostate specific antigen 1.55 ± 1.72 ng/ml). The average percent prostate specific antigen increase from baseline was higher in group A (21.9%) than in group B (14.1%). Overall the greatest prostate specific antigen was observed after 1 month of treatment and decreased thereafter.

CONCLUSIONS:

Patients with baseline total testosterone less than 250 ng/dl were more likely to have an increased prostate specific antigen after testosterone replacement therapy than those with baseline total testosterone 250 ng/dl or greater, supporting the prostate saturation hypothesis. Clinicians should be aware that severely hypogonadal patients may experience increased prostate specific antigen after testosterone replacement therapy.

Last edited by a moderator: