Vince

Super Moderator

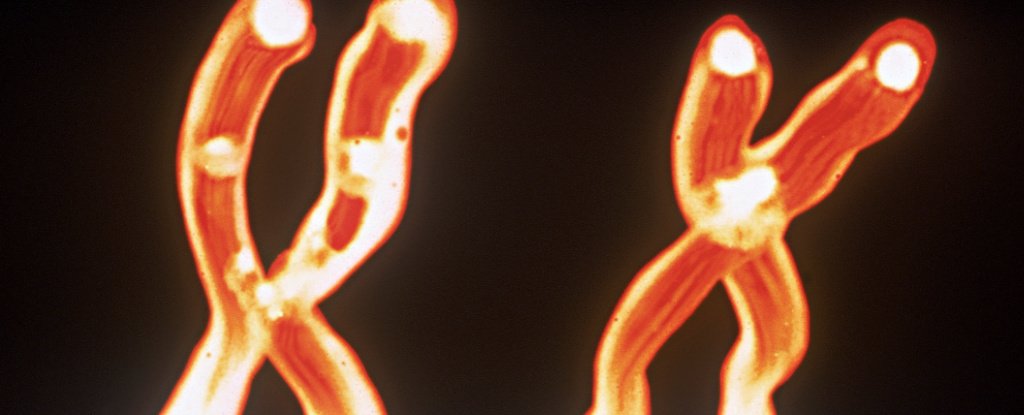

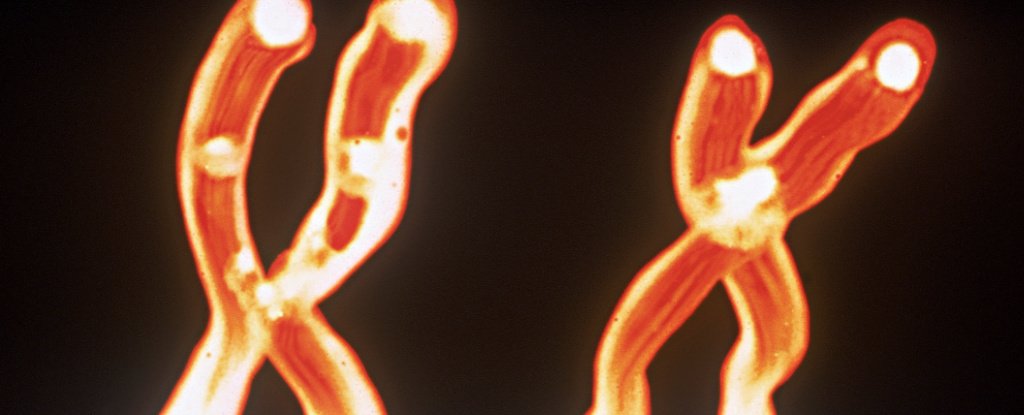

One example of this is a condition whereby white blood cells are missing their Y chromosome. Called mLOY (for mosaic Loss Of Y chromosome), it's more common than you might think, occurring in roughly 40 percent of men aged over 70.

Although the Y chromosome has long been considered a shrinking genetic wasteland full of dispensable chunks of DNA, missing a Y chromosome can have serious health consequences.

In epidemiological studies, mLOY has been associated with shorter lifespans and a greater risk of age-related diseases, such as cancer and Alzheimer's disease. Now, the condition could also be linked to impaired heart function, according to a new study mimicking the human condition in mice.

For a while it has been unclear how losing the Y chromosome from blood cells leads to organ damage and disease in other parts of the body, and ups the risk of age-related maladies, particularly cardiovascular disease and stroke.

The team of researchers led by cardiovascular researcher Soichi Sano of Osaka Metropolitan University Graduate School of Medicine in Japan, probed those questions a little deeper, and have shown how mLOY triggers tissue damage that leads to heart failure in mice and is linked to cardiovascular disease.

In the study, the researchers used the famed gene-editing tool CRISPR to engineer mice with no Y chromosomes in their white blood cells to mimic the human mLOY condition.

The CRISPR-ed mice lived shorter lives than unaffected mice, and had increased scarring of the heart, a condition known as cardiac fibrosis that stiffens heart tissues and is linked to heart failure.

"We see that mLOY [in mice] causes the fibrosis which leads to a decline in heart function," says geneticist and senior author Lars Forsberg of Uppsala University.

To test those findings against epidemiological data, the researchers then analyzed data from the UK Biobank, a decades-long study that has captured genetic and health information of some half a million typically aging adults.

They found men with mLOY in their blood at the start of the study had an increased risk of dying from heart failure and other types of cardiovascular disease during the on-average 11 years of follow-up.

"This observation is in line with the results from the mouse model and suggests that mLOY has a direct physiological effect also in humans," says Forsberg.

www.sciencealert.com

www.sciencealert.com

Although the Y chromosome has long been considered a shrinking genetic wasteland full of dispensable chunks of DNA, missing a Y chromosome can have serious health consequences.

In epidemiological studies, mLOY has been associated with shorter lifespans and a greater risk of age-related diseases, such as cancer and Alzheimer's disease. Now, the condition could also be linked to impaired heart function, according to a new study mimicking the human condition in mice.

For a while it has been unclear how losing the Y chromosome from blood cells leads to organ damage and disease in other parts of the body, and ups the risk of age-related maladies, particularly cardiovascular disease and stroke.

The team of researchers led by cardiovascular researcher Soichi Sano of Osaka Metropolitan University Graduate School of Medicine in Japan, probed those questions a little deeper, and have shown how mLOY triggers tissue damage that leads to heart failure in mice and is linked to cardiovascular disease.

In the study, the researchers used the famed gene-editing tool CRISPR to engineer mice with no Y chromosomes in their white blood cells to mimic the human mLOY condition.

The CRISPR-ed mice lived shorter lives than unaffected mice, and had increased scarring of the heart, a condition known as cardiac fibrosis that stiffens heart tissues and is linked to heart failure.

"We see that mLOY [in mice] causes the fibrosis which leads to a decline in heart function," says geneticist and senior author Lars Forsberg of Uppsala University.

To test those findings against epidemiological data, the researchers then analyzed data from the UK Biobank, a decades-long study that has captured genetic and health information of some half a million typically aging adults.

They found men with mLOY in their blood at the start of the study had an increased risk of dying from heart failure and other types of cardiovascular disease during the on-average 11 years of follow-up.

"This observation is in line with the results from the mouse model and suggests that mLOY has a direct physiological effect also in humans," says Forsberg.

Many Men Lose Y Chromosomes as They Age. Now We May Know Why It's So Deadly

Errors in the human genome are a part of life.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/15090560/7179437670_9bca616029_b.0.0.1417712369.jpg)